Sunday, July 30, 2006

Glassula and Goebbels

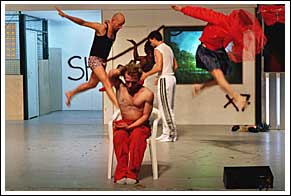

Over the years, Goebbels has come to embody a unique combination you could call music-theater—not musicals, but a hybrid combination that's like an equivalent to the dance-theater embodied by Pina Bausch. He integrates music into thought-provoking spectacles that are never less than visually striking. It's a tough combination to achieve, especially since the visuals are more than surface: For Goebbels, they are part of the very fabric of the show, of the intellectual concept even.

In Eraritjaritjaka, André Wilms spoke all the words (pulled from Elias Canetti's writings—hence, perhaps, the subtitle) while the Mondriaan Quartet played pieces ranging from Ravel and Bach to Gavin Bryars and John Oswald. Halfway through, and just as we were getting used to what looked like yet another European import mixing portentous aphorisms, classical music and elegantly minimalist staging, Wilm left the stage. Actually, we know he left the building since he was followed by a cameraman who continuously filmed him (the image was projected onto the white facade of a house onstage) as he got on then off a cab, bought a bottle of water in a supermarket, entered a building then an apartment, cooked an omelette, etc. But where was Wilms? Unlike the Times' Bernard Holland, I won't spoil the surprise. Suffice it to say that the show had suddenly turned into a metaphysical thriller as Goebbels brilliantly scrambled our expectations in a wizardly technical trick that looked as if he was playing with time and space.

File under What Were They Thinking: Sitting behind me was a mother and her two tween girls. While I love the idea of exposing kids to high art, this was really not a play for children. Needless to say, they quickly got bored and restless, and the trio had to make a hasty departure—and since there was no intermission, it was a hassle for everybody around them. What could that woman possible have thought? "A high-concept show in French and based on Elias Canetti? Move over, Lion King!"

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Walter Hill's juvenilia

Hill was on a roll at the beginning of his career: He followed The Driver with The Warriors, The Long Riders and Southern Comfort, all of them superior examples of 1970s action filmmaking but also alluring examples of a gifted director entertainingly playing with specific movie archetypes. But then he seemed to lose interest in style and delivered straight-faced formula: With 48 Hours and Red Heat (I won't bother to link to these two), Hill bears a lot of responsibility for the horrible buddy-movie craze that took off in the 1980s.

[title of post]

While its kind of mise en abime isn't new, [title of show] is different from, say, Urinetown, in that it doesn't confuse irony and cynicism: Bell and Bowen wrote a love letter to the musical theater (it's larded with references to actors and shows), whereas Urinetown's Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis behaved like wannabe hipsters trying to look cooler than the field they've chosen to evolve in—it seems particularly shallow to deride musicals while cashing in with one at the same time.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Disco satori

Another kind of dancing this time, as I plug Disco Delivery, a music blog out of Calgary dedicated to classic examples of that most derided of genres. I thought I knew my 1970s disco, but to my delight Disco Delivery makes me feel like a rank amateur. You'll have to read every entry and discover the songs on your own, but so far I've been really blown me away by Beautiful Bend, one of the many projects of Russian-born producer Boris Midney. I won't rehash what Tommy (no last name) wrote, and only will add that "Ah-Do It" has got to be the most intoxicating track I've heard in a while. Its single-minded thrust is broken only by a short melody line played on an electric piano—it's like Motorik disco. Adorning it are hypnotically repetitive vocals, bumping percussion, life-affirming horns, sweeping strings and…is it really a harp here? Is that a wah-wah guitar squeak there? There's a lot going on, but it never feels it's too much.

Actually, "Ah-Do It" is only one of the most intoxicating tracks I've heard in a while: The other is Tom Moulton's mix of Claudja Barry's "Love for the Sake of Love," also posted on Disco Delivery. (Tom Moulton was one of the DJ-producers who shaped New York's nightlife in the 1970s. More info on him in Tim Lawrence's Love Saves the Day—A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970–1979.) The song's dreamy sensuality is carried by strings beamed in from an outer galaxy and a moodily restrained vocal by Barry. Love here is not a matter of the flesh; it's a disembodied emotion that's more about gauzy wistfulness than anything else. At 5:52, things bloom into quiet euphoria. We're light-years away from the current take on disco, whether it's made by synthetic Italo clones or the manly likes of the DFA: The kind of disco on these two tracks is both highly theatrical and floatingly self-reflective as it basks in its own soft-lit glow. (Side note: While these songs sound fantastic on headphones, I'm really curious to hear what they'd be like on a good PA.)

Saturday, July 22, 2006

Dance the night around

Some thoughts on Batsheva Dance Company's Telophaza (seen at the New York State Theater Thursday evening), especially in light of Alex Ross' great piece about Mozart, "The Storm of Style," in The New Yorker.

Telophaza was my third Batsheva show, and with 38 dancers it was closer in scale and spirit to Anaphaza (2003, same venue) than the intimate Mamootot, a piece for nine dancers done in the round last year at the Mark Morris Dance Center in Brooklyn.

The first impression is that seeing such a large troupe on stage is thrilling, especially since Batsheva choreographer Ohad Naharin knows how to move it. You'd think moving a large group of dancers shouldn't be such a big deal, but anybody who's seen Broadway ensembles clunkily roam about a stage can tell it's not. The comparison with Broadway isn't as far-fetched as it may seem because while Naharin's vocabulary and artistic aim are completely different, a lot of his large-scale work is audience-friendly in a fundamental way; but while it's easy to enjoy on a gut level, it also contains sophisticated layers of possible interpretation ready to be peeled off by audience members keen on analysis.

In a different style, of course, Telophaza captures some of what makes Mozart's greatest achievements so great and so enduring. In a letter to his father quoted in Ross's article, Mozart writes of some of his concertos: "There are passages here and there from which the connoisseurs alone can derive satisfaction; but these passages are written in such a way that the less learned cannot fail to be pleased, though without knowing why." You could enjoy Telophaza on a purely surface level—it was never less than gorgeous eye candy, again, an achievement not as easy as you'd think—but you could also ponder, for instance, Naharin's use of video closeups (is technology indispensable to draw the viewer in? Does closeness necessarily equate intimacy?).

Another Naharin particularity is his occasional recourse to audience participation. While it's a device I generally dislike (cheap pandering!), somehow I don't mind it in his pieces. In Telophaza, a disembodied voice belonging to "Rachel" gave us instructions, which we were meant to follow from our seats, like:

"Put your hands in front of your face."

"Put a hand on your head and count down to yourself from ten to one."

"Place your hand on your mouth and think of what you ate today."

"Put both hands on your stomach and think about who you miss."

"Put your hands on your thighs and think that you have plenty of time."

People chuckled, but they also did as told. Because nobody was singled out, as tends to be the norm in audience participation, the sense of community was striking.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Censor! Censor!

I have mixed feelings about this affair. In his quality of administrator, Bozonnet is entitled to add or withdraw productions. Cries of censorship feel overdramatic and almost exploitative—since after all anybody is still free to mount the play—not to mention that they allow Handke to wrap himself in a convenient mantle of self-important martyrdom. At the same time, Handke has never hidden his sympathies, something Bozonnet clearly should have thought about before programming the Austrian writer.

This hits close to what happened to My Name Is Rachel Corrie and New York Theater Workshop a few months ago. I do believe NYTW artistic director Jim Nicola wasn't wrong to withdraw the play from his schedule, just as I believe he could have handled the matter better. In the end, another theater, like for instance the Culture Project at 45 Bleecker, could conceivably put on the play. And would people have been as upset if Nicola had said something along the lines of, "My bad: I finally read the play and it's a didactic piece of crap so we won't produce it after all"? Like his initial move, it would have displayed bad judgment (think before you program something!) and even worse diplomatic skills, but I doubt it would have created the same uproar.

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

"We called them saloons. Toilets. Dives."

Could there be a more entertaining read than James Gavin's Intimate Nights—The Golden Age of New York Cabaret? The rogues gallery in the first couple of chapters alone is mind-boggling, and often laugh-out-loud funny. My favorites tend to be the now-forgotten ones, like Sheila Barrett, an impressionist wildly popular in the 1930s, and whose routines "included a scene from Hamlet as it would have been enacted by Bert Lahr and Lynn Fontanne; Mae West as Juliet; and Fanny Brice as Scarlett O'Hara opposite W.C. Fields as Rhett Butler." Or Ray "Rae" Bourbon, a female impersonator who peaked in the 1930s and 1940s before spinning into oblivion and meeting a sad, bizarre ending (let's just say it involves a pack of 15 dogs in a trailer and an alleged hit on a pet-shop owner).

Intimate Nights documents a period of New York nightlife that seemed to brass all kinds of people in a rare manner. The photo of "the Reno Sweeney family, 1974," in particular, makes my head spin: Marta Heflin, Baby Jane Dexter, Ellen Greene and Marilyn Sokol are side by side, but wait! There's also Patti Smith and Holly Woodlawn! An equivalent would be the way races and sexual orientations mixed through disco in the mid- to late 1970s.

In addition to a veritable goldmine of hilarious anecdotes and often touching portraits, Gavin also deals with the integration of homosexuality on stage and off, and the way it shaped both identity and show business; the early acceptance of black performers; and the intangible bond between song, performer and audience. The latter are perhaps more inextricably linked in cabaret than in any other pop genre, often to the point of discomfort for both audience and musician.

In this and many other ways, cabaret is as rebellious as rock & roll—and unlike rock, cabaret has no hope of ever commodifying its dissent; it is a minority taste. Some of it took place in Loudon's saloons, toilets and dives, far from the pop/consumerist mainstream. Some of it unfurled in swank venues, but it still mocked, in song and deed, the Good Housekeeping/K-Mart aesthetics, heterosexual missionary position and clean Christian habits endorsed by the majority of America. Then and now, it's hard to think of a American art form populated with a bigger bunch of geeks, freaks and perverts than cabaret—and I say that with utmost affection, of course.

Monday, July 17, 2006

The sound and the fury

On Friday night, Emperor put on one of the most unrelenting shows I've ever seen; I left B.B. King's in a daze, barely able to walk to the subway on my weakened legs. I wholeheartedly agree with my colleague and friend Steve Smith's description, and only have a few thoughts to add. One of the things I enjoy most about black metal is its buzzy petulance, the way guitars swarm around your ears like maddened bees. Emperor had plenty of that, but intricate, grand song structures as well, which injected a sense of careful planning into a general atmosphere suggesting end-of-the-world chaos. The mix of screeching abandon and Napoleon-like plotting makes black metal incredibly vital live. That and the unbelievable, head-pummelling aggro, of course.

Sunday night was Grendel at the New York State Theater. I feel as if I'm the only person in town who was bored by Julie Taymor's Magic Flute at the Met, and Grendel elicited the same reaction. The problem with Taymor is that she sucks all extremes out of art. In The Magic Flute, everything was lukewarm: The sad scenes weren't sad enough, the joyous scenes weren't joyous enough, and so on. Taymor is the queen of the middle road—and middle brow—as if she were afraid of anything that'd send the emo-meter not even into but toward the red. Elliot Goldenthal's score for Grendel never raised above basically competent (at best), and Taymor's staging didn't help, since it never developed into actual drama, just an ersatz of it. (Special kudos to Denyce Graves for looking—and at times sounding—like Eartha Kitt, though.) Using puppets to depict Grendel's attackers ensured that the violence was so stylized that it didn't hit us in the gut. All we saw was puppeteers clad in black, bunraku-style, swarming around holding what looked like toy soldiers. The effect was entirely devoid of danger, pain, aggression. It was just…pretty. And pretty is what you get at the American Girl daily show, not the opera.

Friday, July 14, 2006

The Wooster Group vs. the Green Goblin

And based on the op-ed Martel (who was cultural attaché in the US for several years) just wrote in the French weekly Les Inrockuptibles, there will be plenty to talk about. Titled "How Mickey Stepped on American Theater" (a very French statement), it looks like a summary of the book's main arguments, including the fact that American theaters had to fight the decline in popularity of their artform by practicing "outreach"—grassroots creations and marketing, including engaging specific communities (gay, Latino, etc.) That's certainly one answer to the problem, though it is incomplete.

A few sweeping statements irritatingly creep in here and there. For instance, Martel writes, "Here's the era of The Lion King in theaters which yesterday hosted Arthur Miller and Peter Brook." While he's not on Broadway, Brook is still staged in NYC; as for Miller, he is very much still represented on the Great White Way.

An indication of a possible (again, typically French) misreading of the relation between art and commerce in the US is an aside stating, as an example of American theater's losing battle against mass culture, that the Wooster Group gave in to "the sirens of the cultural corporations" when Willem Dafoe played the Green Goblin in Spiderman. First of all, the Wooster Group had nothing to do with Spiderman; Dafoe acted (in both senses of the word) on his own behalf. In addition, not only did he appear in the Wooster's revival of Brace Up!, at about the same time (2002), but by then he had spent two decades appearing in both Wooster shows and Hollywood movies.

Dafoe's film career probably helped subsidize the downtown company, which in turn kept him engaged in the experimental world. In a country where there is little public funding for the arts, Hollywood is a de facto benefactor, the actors' fat film paychecks affording them to do theater. The responsibility then falls on the actors themselves to choose good stage material. Some play it safe, choosing staid vehicles; others are more daring: For years Elizabeth Marvel—one of NYC's top stage actors—funded her Off and Off-Off career with a regular gig on the TV drama The District. On the other hand, Allison Jeanney completely disappeared from the stage after becoming a regular on The West Wing.

Of course, this leads to the question of why actors can't make a decent living on stage and need to do film and TV work. Yes, a few people earn quite a decent buck on Broadway, but that's because the Broadway system is powered by $250 premium seats and $100 second-balcony seats, and of course no discounts for students and seniors. There has to be a way for people to make a living working Off and Off-Off full-time. NYC theater insiders may scoff, but the crisis of the American theater will never be resolved if the only way to make a living in theater is by being on Broadway.

But more on this later. I must prepare myself to finally see Emperor tonight. It's the equivalent of a Beatles reunion for black-metal fans.

Thursday, July 13, 2006

How to be a "modern" girl group

"The three vocalists - one brunette, two blondes - offer a modern spin on classic girl groups: the Shangri-La's, the Marvelettes and the Chiffons." So far, so good, even though the Pipettes tunes I've heard are as unabashedly retro as a Civil War reenactment.

But then: "Their songs seem to have been blasted from a golden age of the Brill Building, Phil Spector, sugary harmonies and doo-wop - but with a contemporary, slightly feminist slant. Most concern nasty boyfriends, or boring boyfriends dumped for being 'too sweet', and there's a streak of prudity in Judy, about a girl who did 'rude things'."

That old canard again! Anybody with half an ear knows that many Brill Building songs—the biggest influence on the Pipettes—did, in fact, have a "slightly feminist slant" (something observed as early as 1989 by Charlotte Grieg in her clever book on girl groups, Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?) And the Pipettes' boyfriends aren't dumped for doing too much meth or getting nasty with Lindsay Lohan, but for being "too sweet." A modern spin, indeed.

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Chunky thoughts

I Want to Dance Better at Parties is based on—and integrates—interviews Obarzanek conducted with five men of various backgrounds, who talked about their relationship with dance, from clogging to ballroom. And that relationship isn't always easy, leading to the representation of "bad" dancing by people who obviously are "good" dancers. The representation of ineptitude on stage usually is tricky because the faking tends to be glaringly obvious. In this case, Obarzanek cleverly got around it by limiting the intentionally awkward movement and focusing on the visual representation of the men's personalities as well as their interaction with their bodies and those of others. Not sure he succeeded, but the attempt was interesting.

I also loved watching one particular dancer (I believe it was Antony Hamilton) because it's always interesting to see how short men move on stage, specifically when it comes to interacting with women and other (usually taller) men. The results often seem to involve either intentional comedic distance or bravado. Hamilton eschewed both.

Speaking of senses working overtime, I just got notice of Meet the Composer's forthcoming commissions. Several look exciting, including Eve Beglerian and David Neumann's Feed Forward, a dance based on popular sports; My Name Is Blackbird, a dance solo for Molly Shanahan scored by, among others, violinist and whistler extraordinaire Andrew Bird; and Phil Kline and Wally Cardona's Intime, which will explore "the dramatic potential of a full-size high-school marching band." As a huge fan of marching bands, I am thrilled. Even better, the piece will be workshopped at the Myrna Loy Center in Helena, MT, next year. Any city with an arts center named after Myrna Loy ("Montana's first lady of film") deserves a visit.

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

Avignon–New York

The Festival d'Avignon has just started. Just check out its program and compare it with what we're getting at the Lincoln Center Festival. Fine, I understand bringing over Zingaro would make the Lincoln Center's coffers explode (our favorite uptowners are probably still paying some of the bills incurred last year by Théâtre du Soleil's epic, fantastic Le Dernier Caravansérai), but surely it can't be that expensive to produce something by Edward Bond, whose work is scarce in New York. And I can't fathom why LC isn't inviting Alain Platel and his Ballets C. de la B. The company is travelling to Montreal, Ottawa and Mexico City this year, but no sightings in the US. Instead, it'd be easy to think that Mark Morris and Ohad Naharin are the only two choreographers LC likes enough to invite over and over and over.

Or perhaps BAM could book Platel (whose Wolf is pictured) instead of—or in addition to—the increasingly jejune Pina Bausch. I understand she sells tickets but we need new blood, people! When was the last time a BAM or Lincoln Center Festival show made your stomach lurch, either in agony or in ecstasy? We got spoiled with Théâtre du Soleil in 2005, but this should make us even more nitpicky as we demand of our so-called cultural institutions that they kick the anthill of diminished expectations.

I have no idea how my mind jumped from the LC Festival to this, but the new Justin Timberlake single, "SexyBack," is disappointingly half-baked. Timbaland is obviously trying to build up on his Nelly Furtado success, but this new collaboration only comes across like a male version of Avenue D—except not nearly as fun. The Timbalake sounds as if it's trying way too hard, which is the exact opposite of sexy, front or back.

Monday, July 10, 2006

Freeze frame

Ah, the vagaries of being stuck in New York when three of my favorite filmmakers happen to be exhibited in Paris: Jean-Luc Godard at the Centre Pompidou (a.k.a. Beaubourg), Agnès Varda at the Fondation Cartier and Pedro Almodóvar at the Cinémathèque Française.

Of the three, the most talked-about show has been, predictably enough, Godard’s. After a disagreement with Beaubourg, which didn’t want to set up some of the rooms to God’s specifications, the director chose to leave them in a state of chaos: exposed electrical wires, unfinished walls, etc. Still, plenty of the usual non sequiturs and flashes of inspiration have survived—even if more often than not that inspiration leaves the viewer baffled. This is what happens when you don’t have to justify anything you do or say.

Almodóvar’s show, like Godard’s, coincided with a full retrospective. The Spanish director followed it up by setting up a series of theme rooms displaying his influences, various drawings, sketches, etc. There seems to be nuns doing the things nuns do in Almodóvar’s movies (is the one depicted above inhaling holy water?) as well as the expected high-contrast portraits.

Varda doesn’t have Godard’s innovative genius or Almodóvar’s current cachet, but she’s always displayed a keen documentarian’s eye, even in her feature films, and of the three she’s the one I’d trust the most with engaging visitors on a specific topic. (Am I betraying an ingrained conservatism here?) Her show, titled L’Île et Elle, is based on Varda’s time on Noirmoutier, an island off the coast of Vendée where she’s had a house for ages. Interviewed recently on France Inter radio, the tireless Varda talked delightedly about exploring mixed media for her installations—“Ping Pong, Tong et Camping” is a short film screened onto an inflatable mattress for instance.

When a filmmaker gets museum space in the US, it always seems to be linked to a pandering $$$ machine along the lines of “The Art of Star Wars,” where the director’s vision is undistinguishable from its merchandizing impact. (It would be fun to see some Godard-inspired trinkets though: the Weekend Happy Meal, the Masculin Féminin action figure/doll combo.) Which American director could handle museum walls? Martin Scorsese is an obvious choice, but he’s also too obvious; I’d be more curious to see what Michael Mann or Terrence Malick would come up with.

Saturday, July 08, 2006

Six characters in search of a translator, part 1

Amazingly Les Clients lived up to that description. It follows the various characters who reside at the Central Hotel, including the owner, Madame Poteau, addicted to cocaine and occasionally sleeping with a prostitute who lives at the hotel; a French woman nicknamed Lily Marlène because she sleeps with the enemy; the wife of a resistant, who ends up raped three times by French men who used the chaos of the liberation to pillage and abuse. And so on. This novel is as good—meaning as gloriously nasty, relentlessly bleak—as a vintage Georges Simenon. (Allow me here to refer to one of my own reviews.) Simenon and Héléna make Neil LaBute feel rather quaint in comparison.

As it turns out, Héléna was a rather prolific pulp writer in the post-WWII years. Like many of his peers, he mostly focused on noir but also wrote a series of erotic novels. (And again like so many French pulp writers of that time, he used a lot of pseudonyms, many of them—such as Andy Helen, Kathy Woodfield or Patricia Wellwood—American/English-sounding.) E-dite Editions, in Paris, has reissued several of his books. If they're as cruel, as unsentimental—and as deserving of an English translation—as this one, Héléna is among fiction's most unjustly neglected dark gems.

A slow start

Does understatement befit Macbeth? Does the play necessarily need a Sturm und Drang staging to work, actors whose faces are frozen in maniacal expressions as they wash imaginary blood from their hands and descend into madness? At the Public Theater's production of the Scottish play in Central Park a few nights ago, I was reminded that it is a viewer's duty to battle preconceptions when watching a performance, be it theater, music, dance, a movie or the most minimal of readings. Was I disappointed because I could not fathom a Macbeth in which the leads (in this case, Liev Schreiber and Jennifer Ehle) play inward rather than outward? Or was I disappointed because I read their potential act of subversion as dull, not daring? Schreiber is an actor with keen instincts, and I find it hard to believe he didn't accomplish exactly what he set out to do—or what director Moisés Kaufman instructed him to do; it was puzzling to see him so pallid.

A first step in thinking about this is the directorial problem that's destroying New York theater; it's a problem I clearly spend way too much time thinking about. Our city's scene is plagued with an abundance of hacks with no imagination and no ambition, grovelling servants indebted to both their moneybag masters and audiences assumed to be braindead. Let's not even get into the utter lack of any kind of artistic intent: Do these so-called directors even have the minimum amount of know-how required to oversee a show? Why would Kaufman even tolerate the embarrassingly amateurish performances of Teagle F. Bougere and Sterling K. Brown as Banquo and Macduff, respectively?

Thinking back to memorable Shakespeares I've seen, it's obvious that both very traditional and very experimental approaches work, and that the result doesn't hang on the actors' skill (sorry, actors!). Among my favorite are two completely different productions of King Lear. The first was staged by Ingmar Bergman at the Théâtre de l'Odéon in Paris, around 1984 or 1985. It was in Swedish with no surtitles or simultaneous translation, and while I admit that I don't remember specifics, the overall feeling of being powerless while being completely sucked in visions (those of Bergman and Shakespeare) crashing together remains vivid in my mind. It's a feeling of surrender I've been looking to capture again ever since, what drives me back to the theater again and again and again.

Spectators fled Needcompany's King Lear at BAM in droves in 2001; I still hear the snap of seats being released as people abruptly got up and left during the show. They wanted to make a point, they wanted everybody to hear how displeased they were. The play had been imploded from inside, Jan Lauwers tearing it apart like the alien coming out of John Hurt’s chest. That Lear was grandiosely insane, unpredictable, dangerous. What the hell was Lauwers doing? I’m still not sure, but then, I like being baffled at the theater—a state of mind producers are afraid of eliciting in their audiences, but one I find preferable to benign contentment.

This somehow makes me think of Deborah Eisenberg's Twilight of the Superheroes, which I'm currently reading. Eisenberg's usually praised as a perfect stylist, and she is—every story, every sentence is crafted like a Delft miniature. But how luminously dull that perfection is.