No time to post in Paris as I was busy rediscovering the city on foot (biggest change: the enormous amount of people on bicycles and the effort spent on building new bike paths), spending hours reading the paper in cafés, talking politics with friends (go Ségolène!) and going to the movies. A quick rundown:

- Christophe Honoré's Dans Paris, greeted by very positive reviews, including constant positive nods to the way Honoré honors the New Wave. And he really shoves it down our throats: a direct visual reference to Truffaut's Domicile Conjugal here, a female character named Anna there, and especially Louis Garrel's character, a sub-Jean-Pierre Léaud who didn't get the memo about how Antoine Doinel is meant to remain endearing even when he's irritating. The scene in which Romain Duris and Joana Preiss sing to each other on the phone is really moving, however, a successful Demy pastiche. But the movie tries too hard to be quirky, to be touching, to simply be. Add an awful jazz-lite score and painfully ugly cinematography, and you're left with a piece that does not bode well for French auteur cinema.

- Equally disappointing in a completely different way is Rachid Bouchareb's Indigènes, which won its four lead actors an interpretation prize in Cannes. The movie is about men from the French colonies of North Africa fighting in the French army in 1944-45, and a typical example of how meaning well does not often translate into making good. The actors are indeed excellent, though there's a credibility gap as wide as the Grand Canyon at the center of the movie: Jamel Debbouze has a lame right arm and there's no way a man with only one functional arm would have been accepted in the army, and he certainly would not have been sent to battle with a rifle. To have Debbouze in the part does not make sense, and his handicap is never addressed in the film. Insane! From there on I could not take the movie as seriously as it deserves to be taken.

- two Frenchy-French-French comedies: Eric Rochant's L'école pour tous and, er, some no-name director's Poltergay. Both are ripe for American remakes, though only the former is likely to remain the better version. In L'école pour tous, a banlieue dude poses as a French teacher in a middle school smack in the middle of an at-risk neighborhood in order to evade the police. Various shenanigans and hilarity ensues. The best part of the movie is that the main character does not really improve at the end and does not miraculously become a brilliant teacher. The second best part is director Noémie Lvovsky stealing every scene she's in as a flamboyant fellow teacher. Poltergay benefits from a brilliant title and premise (in addition to Clovis Cornillac's pecs, wasp's waist and excellent comic timing): a couple moves into a house haunted by the ghosts of five gay men who died in a disco fire in 1979. Only other men can see them. Genius! The execution does not always follow but there's nothing a team of Hollywood rent-a-hacks couldn't fix.

- Les honneurs de la guerre, a 1960 movie set in 1945 and scripted by future director Jean-Charles Tacchella. No music, very odd mood for this UFO of a film in which the French villagers are shown as pretty deluded and pathetic, especially the eleventh-hour resistants.

As a side note, going to the movies in Paris is an exquisite pleasure: The screening conditions are generally nice (and often superb) and the silence among the audience nearly absolute. None of that constant bovine munching that accompanies movies in the US, and which I am completely fed up with.

Hey, time for Desperate Housewives dubbed in French! Next post: Heiner Müller's Quartett.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Solar systems

I'm swamped with work before going on vacation so this will just be a brief plug for two recent Time Out reviews:

I'm swamped with work before going on vacation so this will just be a brief plug for two recent Time Out reviews:• the new Sofie von Otter CD, dedicated to the music of Benny Andersson. I wish I had liked it more since her cover of Abba's "Like an Angel Passing Through My Room" was a highlight of her collaboration with Elvis Costello, For the Stars. Still, it's nice to hear a song from Benny's underrated album Klinga Mina Klockor. Coincidentally I finally saw Mamma Mia! the same week I wrote this review. It was weird to hear all those Abba songs in a different context, i.e. to have them work as devices serving a narrative, and the show's relentlessly bright aesthetics can be tiresome, but Carolee Carmello does a great job as the mother, particularly when she wrings every last drop of outsize tragedy from "The Winner Takes It All."

• the new Solar Anus anthology, which collects this Japanese band's entire recorded output. Psych bands are jam bands for the hipster set and they tend to annoy me after a while—it probably would help if I smoked pot—but this one is relentlessly nuts.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Isabelle vs. Isabelle

A few days after blogging about the two Isabelles (Huppert, left, and Adjani) being on the Parisian stage at the same time—but certainly not the same place—I coincidentally came across a funny article exploring the very same thing. In a Nouvel Observateur piece titled "La guerre des Isabelle" ("the Isabelles War"), Marie-Elisabeth Rouchy details the actresses' rivalry, which goes back to that Brontë sisters movie they made with André Téchiné back in 1979, when their respective agents would time their screen time to make sure one didn't get more than the other. Adjani recalls that Téchiné didn't want them to wear makeup but that they always tried to sneak some on while he wasn't looking so one wouldn't look plainer than the other. (The third sister was played by the wonderful Marie-France Pisier, but you don't see her get into feuds with anybody.)

A few days after blogging about the two Isabelles (Huppert, left, and Adjani) being on the Parisian stage at the same time—but certainly not the same place—I coincidentally came across a funny article exploring the very same thing. In a Nouvel Observateur piece titled "La guerre des Isabelle" ("the Isabelles War"), Marie-Elisabeth Rouchy details the actresses' rivalry, which goes back to that Brontë sisters movie they made with André Téchiné back in 1979, when their respective agents would time their screen time to make sure one didn't get more than the other. Adjani recalls that Téchiné didn't want them to wear makeup but that they always tried to sneak some on while he wasn't looking so one wouldn't look plainer than the other. (The third sister was played by the wonderful Marie-France Pisier, but you don't see her get into feuds with anybody.)More good stuff from the article for non-francophones:

In the late ’70s, Huppert and Adjani both wanted to star in a film adaptation of Théophile Gaultier's La dame aux camélias (usually known here as Camille). Huppert won that one, but Adjani scored a few years later when she got to do a project they both coveted, the life of Camille Claudel.

Even more deliciously (and that I had totally forgotten about), Huppert starred in Schiller's Maria Stuart in London in 1996—the character Adjani is now playing in Paris, but in Wolfgang Hildsheimer's lesser-known version of Stuart's last moments.

Rouchy also tallies the actresses' Césars (Adjani's four to Huppert's one), respective filmographies (Adjani's 27 movies to Huppert's 76) and media profiles (Adjani's breakup with Jean-Michel Jarre lands her in French celebrity magazines, Huppert gets a retrospective at MoMA and a hardcover book of portraits).

Since of course it's more exciting pick a camp, I unhesitantly join the Huppertists—though it's quite fun to watch Adjani vainly try to fight Time and in the process resemble more and more a porcelain doll.

And that's the end of tonight's Star Watch.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Frances Faye revisited

You can't really go wrong with frantic bongos. Within a minute or so of Terese Genecco and her "little big band" taking the stage at the Metropolitan Room Saturday night, and as the manic percussion was launching the festivities, it was obvious the show would generate more wattage—and fun—than an entire evening of Rufus Wainwright at Carnegie Hall.

You can't really go wrong with frantic bongos. Within a minute or so of Terese Genecco and her "little big band" taking the stage at the Metropolitan Room Saturday night, and as the manic percussion was launching the festivities, it was obvious the show would generate more wattage—and fun—than an entire evening of Rufus Wainwright at Carnegie Hall.Following a tip from the esteemed Adam Feldman, we trekked to the Metropolitan Room (a very nice place to see a show, by the way) intrigued by the prospect of a singer brazen enough to pay tribute to Frances Faye, a spirited but now largely forgotten nightclub singer whose career spanned the 1930s–’70s. Most of Faye's dozen albums are out of print, and my introduction to her came only a few years ago through Caught in the Act, which documents a Vegas set complete with oddball banter. Oddly enough, Faye is absent from James Gavin's indispensable book on the New York cabaret scene.

As Genecco makes it clear, she doesn't try to impersonate Faye. Rather, she and her smokin' seven-piece band attempt to recreate the mood at Faye's shows; they use the same arrangements (many by Russell Garcia), replicate some of Faye's nuttier flights of fancies (like tweaking the lyrics to "If I Was a Rich Man" to "If I Had a Kilo") and Genecco actually uses some of Faye's between-songs bawdy banter. During the faster numbers, I was reminded Keely Smith but also of Anita O'Day's hard-swinging Songbook albums of the 1950s and 1960s, especially Anita O'Day Swings Cole Porter with Billy May and Anita O'Day and Billy May Swing Rodgers and Hart (the latter produced by Garcia). Genecco's diction was impeccable and she never got thrown off the runaway-train melodies; unlike Wainwright, who looked and sounded as if he was struggling against the songs, Genecco—who also played the piano on some tunes—was never less than supremely comfortable with the material. And the band looked as if it was having a blast, a statement in and of itself. Let's just hope New Yorkers will catch on enough to make it worthwhile for Genecco and her band to come back soon.

Friday, October 13, 2006

A hell of a show

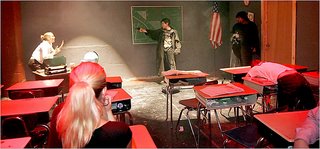

Les Freres Corbusier's Hell House at St. Ann's Warehouse is scary in several ways. The company that gave us Boozy (nominally about Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs, and one of my favorite shows of the past couple of years) bought a $300 Hell House kit from Pastor Keenan Roberts—who makes quite a nice chunk of change by selling them to churches who want to set them up for Halloween—and put it on with a straight face. Small groups of 10-12 people are led through a maze of interconnected rooms by a demon guide and for about 45 minutes we are exposed to what fundamentalist Christians think is scary: a girl is slipped a roofy at a rave, gets gang-raped and commits suicide; a cheerleader endures a bloody abortion; a student guns down his class, Columbine-style; two gay men get married to each other, then one of them becomes sick with AIDS and agonizes on a hospital bed (the doctor wears a yarmulke—nice touch); and so on. The production is pretty much identical to the ones staged all around the Bible Belt (though it would have been even more hardcore to import an actual Hell House complete with Christian extras); the difference is the audience, and how it perceives the Boschian tableaux.

To a proud daughter of the Enlightenment, the scariest part of Hell House is that there are quite a few Americans who take this superstitious nonsense seriously; not only that, but these smug, medieval obscurantists also feel they can tell everybody how to lead their lives. This Hell House may be designed to put the fear of god into fundamentalists—and I can only imagine how it must freak out/screw up a 14-year-old girl in the depths of Oklahoma or Colorado—but it certainly makes my secular-humanist blood boil with anger.

On a side note, Keenan Roberts' approach is very similar to that of fundamentalist cartoonist Jack Chick, whose illustrated tracts are popular kitsch items in many hipster-heathen household. Both men use popular culture to draw in their victims, and both display an uncommon amount of gleeful violence and luridness just as they make a show of demonizing these traits.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Missed opportunities

Considering how good the basic building blocks (book, music) in A Chorus Line are, I was frustrated by the futility of the new revival. I didn't see the original production, but everybody is in agreement that the "new" one is a slavish carbon copy. It was directed by Bob Avian, who co-choreographed the original; Baayork Lee was the original Connie and is now responsible for "choreography re-staging." Sure, it's very entertaining, and large parts of Marvin Hamlisch's score continue to send shivers down my spine, but what's the point?!?

In a weird way, A Chorus Line anticipated the reality-TV boom, with cast members talking to a director (i.e., the camera) in confessional mode, while going through a casting call (i.e. elimination process). It would have been great to dynamite the show and direct it from that perspective, like some kind of razzle-dazzle Big Brother series, but it would have taken producers with balls.

I am told there are legal reasons that A Chorus Line must be staged the same way it always is. This is the death knell for this show: It'll only endure as a period artifact preserved in formaldehyde. It could easily be staged as a biting commentary on a culture driven by ego that's both self-aggrandizing and self-pitying and by competition, but instead it remains a backstage musical frozen in 1975 amber. While this is fine—it's hard not to like a good backstage musical—it could also be…something else. One day, some British director will mount a production of A Chorus Line that brings it into the 21st century, and then everybody here will wonder why nobody had thought of it before. (Look at what John Doyle did to Sweeney Todd.)

The paucity of imaginative directors on the Broadway and upper-Off stages drives me up the wall. What's up with Scott Elliott, for instance? His Threepenny Opera on Broadway was clueless; now his Prime of Miss Jean Brodie for the New Group is a snooze. The play is full of exciting dark corners, especially in the way it deals with the confluence of teaching and domination, and the way it looks at how a charming, charismatic individual can bamboozle students into a miasmic ideology. But Elliott doesn't seem to have any point of view on the story, just as he didn't have any on Threepenny, and he contends himself with letting actors loose, hoping they'll pull through. (And when all else fails: nudity!) Alas, Cynthia Nixon (whose Scottish accent is just bizarre) is out of her depth from the get-go, lacking not only the steely undergirding required to play Miss Brodie, but also the haughty black humor the character displays at times. My neighbor was asleep within 20 minutes; lucky him.

In a weird way, A Chorus Line anticipated the reality-TV boom, with cast members talking to a director (i.e., the camera) in confessional mode, while going through a casting call (i.e. elimination process). It would have been great to dynamite the show and direct it from that perspective, like some kind of razzle-dazzle Big Brother series, but it would have taken producers with balls.

I am told there are legal reasons that A Chorus Line must be staged the same way it always is. This is the death knell for this show: It'll only endure as a period artifact preserved in formaldehyde. It could easily be staged as a biting commentary on a culture driven by ego that's both self-aggrandizing and self-pitying and by competition, but instead it remains a backstage musical frozen in 1975 amber. While this is fine—it's hard not to like a good backstage musical—it could also be…something else. One day, some British director will mount a production of A Chorus Line that brings it into the 21st century, and then everybody here will wonder why nobody had thought of it before. (Look at what John Doyle did to Sweeney Todd.)

The paucity of imaginative directors on the Broadway and upper-Off stages drives me up the wall. What's up with Scott Elliott, for instance? His Threepenny Opera on Broadway was clueless; now his Prime of Miss Jean Brodie for the New Group is a snooze. The play is full of exciting dark corners, especially in the way it deals with the confluence of teaching and domination, and the way it looks at how a charming, charismatic individual can bamboozle students into a miasmic ideology. But Elliott doesn't seem to have any point of view on the story, just as he didn't have any on Threepenny, and he contends himself with letting actors loose, hoping they'll pull through. (And when all else fails: nudity!) Alas, Cynthia Nixon (whose Scottish accent is just bizarre) is out of her depth from the get-go, lacking not only the steely undergirding required to play Miss Brodie, but also the haughty black humor the character displays at times. My neighbor was asleep within 20 minutes; lucky him.

Sunday, October 08, 2006

Everything old is new again is old again

Let's take two completely different offerings: Jay Johnson's The Two and Only on Broadway and Mikel Rouse's The End of Cinematics at BAM. I went to the former expecting little—after all, this was a one-man show by a ventriloquist whose main claim to fame was a recurring gig on the 1970s series Soap; yet I came out not only charmed, but musing about the evolution of popular entertainment, dichotomic acts, acting with voice vs. body. I went to the latter expecting to my brain cells to be activated, my sensory nerves to be tickled; I exited in a semi-catatonic state.

Anybody who's seen a Shakespeare in the Park show at the Delacorte has been subjected to a high-tech form of ventriloquism—the miking is so intense that there's no correlation between the actors' voices and their lips; actors throw their voices whether they want it or not. Jay Johnson does it the old-fashioned way: by projecting his voice onto a puppet (or a tennis ball, or whatever's handy—but usually a puppet) clinging to his arm and by establishing a straight man/demented accomplice act. Think of it as Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin's cabaret routines done by one person. That reference also alludes to these antics' antique style: The Two and Only is a trip back to a long-gone time of radio dramas, Catskills entertainment and variety-show acts. But Johnson pulls it off because in addition to the technical skills that allow him to create genuinely funny routines, he weaves in and out of a narrative touching upon the notion of old-school mentorship and the melancholy inherent in specializing in an art that not only is considered dorky but is pretty much on the verge of extinction.

Composer-director Mikel Rouse has said in an interview with my colleague Steve Smith (referring to the old Cage/Cunningham collaborations and how you could approach his own show in the same manner): "you’ve got permission to check in and check out." Fine, but Rouse's own M.O. prevents that: There's too much going on onstage—a beautiful bilevel stage, projections of images both prerecorded and filmed live, actors-singers interacting with each other and their preshot avatars—and yet none of it is particularly compelling. Why mention in the program notes Susan Sontag's article about the death of traditional cinephilia and call your show The End of Cinematics if half of it relies on purely cinematic tropes? By starting the evening with trailers of upcoming Hollywood productions (Spiderman 3, a CGI version of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles), are you implying that your own show isn't that different in that it's a hollow head trip defined by the technology that allows it?

The first two songs lured me in because I thought that finally a contemporary composer had successfully reached out to the world of pop electronics, but Rouse's inspiration frittered away quickly—all the songs sounded the same and the lack of dynamics was maddening (but then, dynamics would have prevented the kind of daydreaming Rouse claims he was after). Mostly the show reminded me of a jumbled mix of 1960s hippie happening, late ’80s/early’90s rave culture, Wired's wide-eyed love for gadgetry and Laurie Anderson's early work: There was nothing in The End of Cinematics that wasn't in her 23-year-old magnum opus, United States I–IV (created at BAM).

On a more general note, the show fits perfectly into BAM's current programming, which—as my friend Christian (a subscriber who walked out of The End of Cinematics) astutely pointed out—seems to increasingly fall into basic categories: American tech-heavy spectacles (Mikel Rouse, the Builders' Association), European dance-theater (Pina Bausch, Sacha Waltz), versions of classic works by international companies (Macbeth in Japanese, Hedda Gabler in German, Maria Stuart in Swedish, etc.) and neo-trad pieces (the theatrical equivalent to world music). Of course enough of the shows are good, or at least interestingly flawed, that BAM remains an indispensable institution on the NY scene. How else would we have seen Ingmar Bergman's stage work? Who else is bringing over Germany's Thomas Ostermeier, whose Nora (A Doll's House) two years ago was a great example of a flawed but mesmerizing production? Perhaps I'm harsh on BAM because I've been spoiled and now I expect too much from it.

Anybody who's seen a Shakespeare in the Park show at the Delacorte has been subjected to a high-tech form of ventriloquism—the miking is so intense that there's no correlation between the actors' voices and their lips; actors throw their voices whether they want it or not. Jay Johnson does it the old-fashioned way: by projecting his voice onto a puppet (or a tennis ball, or whatever's handy—but usually a puppet) clinging to his arm and by establishing a straight man/demented accomplice act. Think of it as Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin's cabaret routines done by one person. That reference also alludes to these antics' antique style: The Two and Only is a trip back to a long-gone time of radio dramas, Catskills entertainment and variety-show acts. But Johnson pulls it off because in addition to the technical skills that allow him to create genuinely funny routines, he weaves in and out of a narrative touching upon the notion of old-school mentorship and the melancholy inherent in specializing in an art that not only is considered dorky but is pretty much on the verge of extinction.

Composer-director Mikel Rouse has said in an interview with my colleague Steve Smith (referring to the old Cage/Cunningham collaborations and how you could approach his own show in the same manner): "you’ve got permission to check in and check out." Fine, but Rouse's own M.O. prevents that: There's too much going on onstage—a beautiful bilevel stage, projections of images both prerecorded and filmed live, actors-singers interacting with each other and their preshot avatars—and yet none of it is particularly compelling. Why mention in the program notes Susan Sontag's article about the death of traditional cinephilia and call your show The End of Cinematics if half of it relies on purely cinematic tropes? By starting the evening with trailers of upcoming Hollywood productions (Spiderman 3, a CGI version of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles), are you implying that your own show isn't that different in that it's a hollow head trip defined by the technology that allows it?

The first two songs lured me in because I thought that finally a contemporary composer had successfully reached out to the world of pop electronics, but Rouse's inspiration frittered away quickly—all the songs sounded the same and the lack of dynamics was maddening (but then, dynamics would have prevented the kind of daydreaming Rouse claims he was after). Mostly the show reminded me of a jumbled mix of 1960s hippie happening, late ’80s/early’90s rave culture, Wired's wide-eyed love for gadgetry and Laurie Anderson's early work: There was nothing in The End of Cinematics that wasn't in her 23-year-old magnum opus, United States I–IV (created at BAM).

On a more general note, the show fits perfectly into BAM's current programming, which—as my friend Christian (a subscriber who walked out of The End of Cinematics) astutely pointed out—seems to increasingly fall into basic categories: American tech-heavy spectacles (Mikel Rouse, the Builders' Association), European dance-theater (Pina Bausch, Sacha Waltz), versions of classic works by international companies (Macbeth in Japanese, Hedda Gabler in German, Maria Stuart in Swedish, etc.) and neo-trad pieces (the theatrical equivalent to world music). Of course enough of the shows are good, or at least interestingly flawed, that BAM remains an indispensable institution on the NY scene. How else would we have seen Ingmar Bergman's stage work? Who else is bringing over Germany's Thomas Ostermeier, whose Nora (A Doll's House) two years ago was a great example of a flawed but mesmerizing production? Perhaps I'm harsh on BAM because I've been spoiled and now I expect too much from it.

Friday, October 06, 2006

Vivica watch #1

Oh dear, I seem to have acquired a new stage crush. Went to see Handel's Semele at City Opera on Wednesday and became completely obsessed with Vivica Genaux, who sang the dual parts of Ino and Juno. Summoning all my critical faculties and the immense vocabulary at my disposal, I'll offer the following assessment: She's hot hot HOT!

This production of Semele should be forced upon everybody who thinks opera is boring—a more entertaining evening is hard to find in town (at least on that particular Wednesday night, since the performance I caught was the last one). Director Stephen Lawless transposed the action to the early 1960s, with Semele as Marilyn Monroe, Jupiter as JFK and Juno as Jackie K. It was a masterstroke because it fit the plot so perfectly : Ambitious Semele dumps her sensitive (read: countertenor) fiancé for powerful alpha male (duh, he's a god!) Jupiter; meanwhile, jealous Juno tricks Semele into committing a fatal mistake (represented in the show by a pill overdose). The whole thing zipped along for its entire three-hour length, with Lawless always striking a perfect balance between humor and genuine pathos. Sure, Elizabeth Futral didn't sound all that comfortable at times in the title role ("The morning lark to mine accords his note/And tunes to my distress his warbling throat"—warbling throat indeed!) but she barreled through on sheer personality and by acting up a storm. But my heart was stolen by Vivica, who not only looked, er, what I said before, in her little pillbox hat, but also sang rings around La Futral.

Reviewers and bloggers seem to suggest Vivica was mugging and making faces. I have to disagree. The thing, you see, is that technically speaking nothing much happens in a baroque aria. Most of them repeat 2-3 sentences over and over, sometimes in their entirety, sometimes in fragment. (As an aside, I've been musing about how great it'd be if contemporary musical-theater composers took their cues from that style instead of coming up with all these cumbersome, narrative-heavy dirges. I'll refine this thought in a further post.) In addition, and particularly in a case like Semele, it's friggin' impossible to follow the plot without a synopsis because the opera's so elliptical. In order to get the plot moving—and even clarify what was going on—Lawless had those onstage but not singing during an aria move around and, yes, act. Act! Has this become anathema at the opera?!? It made sense for Vivica to act while someone else sang as a way to express what her character was thinking/feeling at any given time, and she never did it in a way that distracted from whatever else was going on; it was just a nice little treat to those paying attention, and it made dramatic sense. It's called reactive acting, people! Too many lazy theater and opera directors focus only on whoever singing/speaking at any given time, leaving those sharing the stage to just stand there. How lazy can you get? Directing doesn't involve only coming up with basic blocking and telling whoever's in the foreground "Now you pretend to be sad/happy/frustrated/angry." Lawless had a concept that fit the opera, then he had his actors interact. Is it so rare nowadays that it can be misinterpreted as making faces?

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Gérard talks

I'm just dying to go on and on about some shows I've just seen (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie at the Acorn, A Chorus Line on Broadway and ¡El Conquistador! at New York Theater Workshop) but I must refrain until my TONY colleagues' reviews come out.

In the meantime, here are a few translated nuggets from a great interview Gérard Depardieu gave to the French weekly Les Inrockuptibles a few weeks ago. The piece is pegged to Depardieu's latest movie, Xavier Giannoli's Quand j'étais chanteur, but it covers his entire career—which, lest we forget, includes movies by owlish French authoress Marguerite Duras and Italian nutjob Marco Ferreri—and Gégé talks like someone who really couldn't give a shit what people think.

• About producing some of his own movies:

"On La Chèvre [1981], for instance, I really felt I got screwed by [producer] Alain Poiré. He didn't want to pay for three plane tickets so that Elisabeth and the kids would visit me on the shoot. And when the movie made millions, he got [director] Francis Veber, [costar] Pierre Richard and myself together and gave us keyrings [laughs]. Well, all right then! (…) Working on La Chèvre was a turning point since before that I was labeled an 'intellectual actor' because I worked a lot with Duras. Yet I always thought of her not so much as intellectual as earthy. And she was a lot more manipulative and grounded than the people who claimed her a genius. But she was a genius, whom we'll still talk about in 500 years. Whereas I'm not so sure about Marguerite Yourcenar, for instance."

• About having to sing in his new movie:

"I learned to sing with [director Claude] Régy. I found it really immodest, I couldn't do it. I had to do it for a Peter Handke play, Les gens déraisonnables sont en voie de disparition. Before that, even drunk it wouldn't have occurred to me. But I learned to do everything on stage. I've even been able to sleep. I woke up, saw Andréa Ferréol, who was only mildly bothered, I waited a beat and went back to acting. I'm telling you about it because I don't think it matters."

• About his relationship with Godard on 1993's Hélas pour moi:

"I remember a chat on a dock in Lyon. We talked for two hours. He kept bugging me with the word star. I told him, 'Truffaut is right, it's normal that you don't have any balls because they've been crushed, but I can't believe how Protestant you are. You're far from being a thug.' Godard's problem is his relationship with money: He wants to get dough, pull off robberies, but then he's afraid. You can't be afraid. When you're paid seven million to make Hélas pour moi without a script, you've got to take them without thinking twice about it."

• About meeting Marco Ferreri:

"The first thing he said to me, with his Italian accent, was, 'Are you temerarious?' I was on my way to pick up some money for expenses, he had just gotten his. All these people were tight with their money. I loved these communists around 1975–76, like Bernardo Bertolucci, who drove a Benz. Bernardo said to me, 'But my Benz is red!' He had a great sense of humor back then. Marco, on the other hand, was a real pain in the ass. He kept it all in, he couldn't even shit. With Marcello [Mastroianni], it really made us laugh."

• About distributing Satyajit Ray's movies:

"I went to India and I wanted to create a Ray Foundation so that his movies would be kept together. I coproduced his three last movies with [Daniel] Toscan du Plantier. I remember that he told me that E.T. was one of his short stories. The biggest hit in American cinema comes from India! He'd sent the script to Columbia way before. When you read it, all E.T. is in there. Of course, no rights were ever paid."

• About Hollywood:

"Hollywood is full of bourgeois. Even worse: Bourgeois who, for the most part, dream they are hoodlums or thugs. A bit like Godard."

In the meantime, here are a few translated nuggets from a great interview Gérard Depardieu gave to the French weekly Les Inrockuptibles a few weeks ago. The piece is pegged to Depardieu's latest movie, Xavier Giannoli's Quand j'étais chanteur, but it covers his entire career—which, lest we forget, includes movies by owlish French authoress Marguerite Duras and Italian nutjob Marco Ferreri—and Gégé talks like someone who really couldn't give a shit what people think.

• About producing some of his own movies:

"On La Chèvre [1981], for instance, I really felt I got screwed by [producer] Alain Poiré. He didn't want to pay for three plane tickets so that Elisabeth and the kids would visit me on the shoot. And when the movie made millions, he got [director] Francis Veber, [costar] Pierre Richard and myself together and gave us keyrings [laughs]. Well, all right then! (…) Working on La Chèvre was a turning point since before that I was labeled an 'intellectual actor' because I worked a lot with Duras. Yet I always thought of her not so much as intellectual as earthy. And she was a lot more manipulative and grounded than the people who claimed her a genius. But she was a genius, whom we'll still talk about in 500 years. Whereas I'm not so sure about Marguerite Yourcenar, for instance."

• About having to sing in his new movie:

"I learned to sing with [director Claude] Régy. I found it really immodest, I couldn't do it. I had to do it for a Peter Handke play, Les gens déraisonnables sont en voie de disparition. Before that, even drunk it wouldn't have occurred to me. But I learned to do everything on stage. I've even been able to sleep. I woke up, saw Andréa Ferréol, who was only mildly bothered, I waited a beat and went back to acting. I'm telling you about it because I don't think it matters."

• About his relationship with Godard on 1993's Hélas pour moi:

"I remember a chat on a dock in Lyon. We talked for two hours. He kept bugging me with the word star. I told him, 'Truffaut is right, it's normal that you don't have any balls because they've been crushed, but I can't believe how Protestant you are. You're far from being a thug.' Godard's problem is his relationship with money: He wants to get dough, pull off robberies, but then he's afraid. You can't be afraid. When you're paid seven million to make Hélas pour moi without a script, you've got to take them without thinking twice about it."

• About meeting Marco Ferreri:

"The first thing he said to me, with his Italian accent, was, 'Are you temerarious?' I was on my way to pick up some money for expenses, he had just gotten his. All these people were tight with their money. I loved these communists around 1975–76, like Bernardo Bertolucci, who drove a Benz. Bernardo said to me, 'But my Benz is red!' He had a great sense of humor back then. Marco, on the other hand, was a real pain in the ass. He kept it all in, he couldn't even shit. With Marcello [Mastroianni], it really made us laugh."

• About distributing Satyajit Ray's movies:

"I went to India and I wanted to create a Ray Foundation so that his movies would be kept together. I coproduced his three last movies with [Daniel] Toscan du Plantier. I remember that he told me that E.T. was one of his short stories. The biggest hit in American cinema comes from India! He'd sent the script to Columbia way before. When you read it, all E.T. is in there. Of course, no rights were ever paid."

• About Hollywood:

"Hollywood is full of bourgeois. Even worse: Bourgeois who, for the most part, dream they are hoodlums or thugs. A bit like Godard."

Monday, October 02, 2006

Deutsch-Französische Freundschaft

A twist on an old German favorite, DAF (Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft), for two German-related items.

• Score! My friend Alexis managed to get us tickets to the Théâtre de l'Odéon's production of Heiner Müller's Quartett, which is based on Laclos' Liaisons Dangereuses. It's staged by Robert Wilson and stars Isabelle Huppert and Ariel Garcia Valdès. I was looking forward to some R&R in Paris in October, and now the trip will be even more interesting. No matter what you think of Huppert, nobody can deny that she takes risks, unlike, I may add, her contemporary Isabelle Adjani, also on the Paris stage but in a rather different vehicle, Marie Stuart—not by Schiller but by an obscure German playwright, Wolfgang Hildesheimer. And to think Adjani played Emily to Huppert's Anne in André Téchiné's Les Soeurs Brontë (1979). Their careers could not have taken more different paths since.

Alas, timing does not only play in my favor, and I'll miss some interesting-looking items in the Festival d'Automne, especially Marcial Di Fonzo Bo's latest evening of plays by Copi, and Romeo Castellucci's new piece, Hey Girl!, which runs in November. Anybody who saw Castellucci's Tragedia Endogonidia: L. #09 London Portrait at Montclair's Kasser Theater last October has got to be dying to see more. Why oh why can't Lincoln Center, BAM or St. Ann's Warehouse bring him and his company, Societas Raffaello Sanzio, over? L. #09 didn't have anything resembling a plot or characters but it was the kind of full-on theatrical experience that remains branded in one's head.

• Read in the latest issue of The Wire that German director Hans-Jürgen Syberberg's 1978 movie Hitler: A Film from Germany is online. You can see it here for $1, which goes toward the restauration of the Nussendorf church tower and is rather cheap for a seven-hour-long reflection on the medium of film as much as on Germany. Syberberg is one of the great directors of the New German Cinema of the 1970s and 1980s, albeit the least well-known in the US. Susan Sontag wrote at length about his masterstroke in The New York Review of Books, starting with "Hans-Jürgen Syberberg's Hitler, A Film from Germany is not only daunting because of the extremity of its achievement, but discomfiting, like an unwanted baby in the era of zero population growth." You need to pay $3 for the rest of the piece, but you can get an idea of its gist based on these letters to the editors, followed by Sontag's response. Her line about how "The need to reduce the work of art to its message obfuscates the character of its artistic lineage" resonates still.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)