What's with that trend of bands playing one of their albums live from top to bottom? My thoughts on the phenomenon in today's New York Times.

The Christmas break has just flown by and thanks to a nasty case of flu I didn't accomplish a single of my goals—go to MoMA, see movies at noon, walk over the Brooklyn Bridge to Chinatown, play Halo while eating delicious Indian sweets from Jackson Heights.

When I was five or six, I got my tonsils taken out in Paris. As soon as I was out of the operating room, my mother, never one to miss an opportunity to see some art, took me to the ballet at the Paris Opera (I'm pretty sure it was Coppelia). Alas, I got sick at intermission and we had to leave; on the way out, I left a trail of crimson-red (I'd been fed strawberry sorbet to soothe my throat) vomit all over the marble staircase. It took me 35 years to be so sick that I'd have to leave a show, which is what happened at yesterday's Ballet Trockadero de Monte Carlo matinee. Right in the middle of Pas de Quatre, I was overwhelmed by a coughing fit worthy of Marguerite Gautier, aka Camille, aka Violetta Valéry; the only option was to leave. So ended my one and only outing in this lost week. What a waste of free time.

Speaking of free time, and perhaps too much of it, Sufjan Stevens has released a box set collecting his Christmas songs over the years. I find Stevens interesting mostly in the context of his relationship with Daniel Smith, the brain behind Danielson; it's touched upon in JL Aronson's new doc on Danielson (which I reviewed for TONY). If Aronson had had more guts, he'd have centered the entire film on the All About Eve connection between Stevens and Smith, and used it to show how the more banal talent gets less recognition than the pricklier one.

Sunday, December 31, 2006

Wednesday, December 27, 2006

20/20 hindsight

Yep, there was quite a bit of good theater in New York this year, and here's what I liked, listed in chronological order:

1. Red Light Winter, by and directed by Adam Rapp, at the Barrow Street Theater. Rapp is moving beyond shock tactics and into craft.

2. BLACKland, devised by Krétakör and directed by Árpád Schilling, at Montclair U's Kasser Theater. A political revue created and interpreted by a super-physical Hungarian troupe. The Kasser is quickly becoming one of the area's most daring venues. But the one thing that depresses me every time I go there is the dearth of students in the audience, especially considering they get free tickets. I guess those cretins would rather be at some sports event.

3. The Wooster Group's revival of its take on O'Neill's The Emperor Jones, directed by Elizabeth LeCompte at St. Ann's Warehouse. Fucking A! This is theater!

4. Measure for Pleasure, by David Grimm and directed by Peter DuBois at the Public Theater. The year's smartest, warmest, most generous comedy. And the most unfairly neglected.

5. The History Boys, by Alan Bennett and directed by Nicholas Hytner at the Broadhurst Theater. Enough has been said about the merits of Alan Bennett's play. But why American directors can't put together anything as kinetic as what Hytner does here is a mystery to me.

6. The Drowsy Chaperone. Lisa Lambert and Greg Morrison's score is delicious pastiche of the old Gershwin/Wodehouse musicals of the 1920s. The show is an oddly intimate experience at the cavernous Marquis Theater.

7. Spring Awakening. I missed the Broadway version but on the Atlantic's small stage Steven Sater and Duncan Sheik's ode to burgeoning teen sexuality was pretty darn cool. And it showed the horrible, embarrassing High Fidelity that rock & roll is a state of mind, not a few hasty references and a couple of dudes in band T-shirts.

8. Eraritjaritjaka. Heiner Goebbels hardly ever disappoints and this year's entry, part of the Lincoln Center Festival, was gripping, using technology in a thrilling way. The Met should get him to direct an opera.

9. Mother Courage and Her Children. Edge-of-your-seat spectacle from the two merrymakers known as…Bertolt Brecht and Tony Kushner?

10. Mary Poppins. Some say it's too long or clumsy or overblown—I don't care. I'm sure the ungainly sight of my jaw hanging fairly low in amazed delight was a turn-off for my neighbors at the New Amsterdam but yeah, I loved it. This is exactly what an all-ages show should be.

But the best thing about going to the theater may well be watching actors at work. Here are my all-stars:

• Julie White in The Little Dog Laughed—but the Off Broadway version, which I found less shrill.

• Kate Valk in The Emperor Jones. The best actor in New York. Only Elizabeth Marvel comes close.

• Christine Ebersole in Grey Gardens. Yeah yeah yeah…but she really is that good.

• Michael Stuhlbarg and Euan Morton in Measure for Pleasure. Stuhlbarg is acknowledged as a great by now, but Morton is turning into a real asset to the New York stage. He was rather cool in Brundibar as well.

• Sherie Rene Scott in Landscape of the Body. She can sing, she can act, she can slink. Old-school sass and an underrated performer.

• Nellie McKay in Threepenny Opera. Watching that show, I could not figure out what the hell McKay was doing. Then I realized she was doing the part filtered through an old Hollywood idea of an ingenue done by someone who can't act. Not sure it worked at the moment, but several months later it sticks in my mind and remains the only thing worth saving from that wretched production.

• Ian McDiarmid in Faith Healer. The play was a snooze (and Cherry Jones was uncharacteristically awful) until McDiarmid came in at the beginning of the second act, with his ratty orange hair and fantastic timing.

• Judy Greer in Show People. Watching the quirky Greer was taking a master class in reactive acting: Even when she wasn't speaking, Greer was in the scene—without mugging to draw attention to herself. It's a fine line, and one she walked beautifully.

• Felicia Finley in The Wedding Singer. A couple of quick in-and-out numbers were enough for Finley to bring down the house. It was fun to watch someone chew the scenery with such gleeful vulgarity.

• Nina Hellman and Jeremy Shamos in Trouble in Paradise. Subtle comedic chemistry from these undersung stalwarts of the Downtown stage.

• Sherry Vine in Carrie. Whaaaaa…???

The year's visuals belonged to the opera, though: Joyce DiDonato going mad in Hercules at BAM; Viviva Genaux and Elizabeth Futral in super-sexy Handelian closeness in Semele at City Center; Madama Butterfly's gorgeous death at the Met. (Note to potential employers of Julie Taymor, however: Stick a fork in her, she's done.)

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

Post-apocalypto

I've always been fascinated by novels and films taking place in a post-apocalyptic world. Give me a small group of survivors trying to make it in a dramatically altered landscape, and I'm happy. I'm not talking about movies depicting the catastrophe itself (ie Deep Impact or The Day After Tomorrow) but about the ones specifically dealing with the aftermath—the nuclear winter of our discontent.

I've always been fascinated by novels and films taking place in a post-apocalyptic world. Give me a small group of survivors trying to make it in a dramatically altered landscape, and I'm happy. I'm not talking about movies depicting the catastrophe itself (ie Deep Impact or The Day After Tomorrow) but about the ones specifically dealing with the aftermath—the nuclear winter of our discontent.Entries in the well-stocked post-apocalyptic genre include novels like Stephen King's The Stand, Nevil Shute's On the Beach, Walter Miller's A Canticle for Leibowitz, Michel Houellebecq's The Possibility of an Island, even Richard Matheson's I Am Legend, and quite a few films: Ray Milland's Panic in Year Zero!, Danny Boyle's 28 Days Later…, Michael Anderson's Logan's Run, Boris Sagal's The Omega Man, Lynne Littman's still-striking Testament (which shows just how much of an emotional punch you can pack with a budget of approximately $12).

On two completely different planes from each other, we can add Cormac McCarthy's The Road and the CBS drama Jericho to the shelf. Neither is hot-off-the-press new, but I'm just getting to them so fine, I'm late.

I'd never been able to finish a Cormac McCarthy book until The Road. His prose felt too affected for my taste—goth for boys—but The Road's stark minimalism actually allows the flights of poetry to support the book rather than choke it. The plot is simple: A man and his son travel through a blighted, ash-covered landscape where nothing grows anymore. They encounter some of the post-apocalyptic staples, like cannibalism and a hidden stash of food, but mostly McCarthy zeroes in on primal emotions and describes incredibly well the abyss the characters face on a daily basis.

Like The Day After, Jericho takes place in Kansas—shorthand, obviously, for all-American. I've only seen the pilot so far but the show looks decent, even though there's a surfeit of hugging. (Hugging has got to be the single most overused—and irritating—gesture in American movies and TV shows. It's a skin-deep show of support that signifies a lot and means nothing.) Jericho follows the Lost formula pretty closely in terms of the group of people it throws in together, down to a hunky-but-broodily-sensitive male lead. What the show lacks so far is that sense of existential dread that permeates the best post-apocalyptic fiction (I'd even include Bergman's Shame in that bunch), as illustrated by the fact that the creators couldn't even bring themselves to let the little girl die on the crashed school bus. Oh well, I'll take Jericho, even if it turns out to be more like Dawson's Irradiated Creek.

Next: Arctic expeditions run amok!

Sunday, December 24, 2006

Will it snow in July?

Will it rain toads? Is this a sign of the impending Apocalypse? In the middle of the latest issue of Vice there's quite a 1-2-3 punch: an excerpt from a text (unpublished novel titled Velvet? unclear) by Andrea Dworkin sandwiched between short stories by Chuck Palahniuk and Neil LaBute. Ka-POW! I mean, I never thought I'd see these names in such close proximity, and in Vice, of all places. And the Dworkin story, nominally about hitting a dog, is the most surprising of the bunch (I did enjoy the other two as well, but their authors deliver exactly what you'd expect from them).

Actually when I first noticed that there was a piece by Dworkin in the fiction issue of Vice, my first thought was that one of the mag's smart asses had written a parody. But the story, "I'm Half Dead" isn't what anybody would consider a "typical" Dworkin screed so it had to be real.

More depressing is the LaBute piece, "Slave to the Office," which somehow aims to make you feel faint pangs of pity for an office bully halfway between asshole and pathetic. Boy has LaBute painted himself into a corner at this point. He has such ease as a stylist, but for what? Cheap effects in the service of devious targets. Still, I keep going back to his stories and plays. It must be nostalgie de la boue.

Palahniuk, at least, achieves a certain 21st-century Freaks-ishness in "Mister Elegant." The take on ideas of normalcy and physical appearance may be only Twilight Zone–deep, but I found the piece's black humor rather effective. It somehow reminded me a bit of what I like in Judy Budnitz's stories. Her work is less anchored in a certain type of hyper-reality, but she also captures the grotesqueries of life.

So there you go: Vice's fiction issue. It's free, pick it up.

Actually when I first noticed that there was a piece by Dworkin in the fiction issue of Vice, my first thought was that one of the mag's smart asses had written a parody. But the story, "I'm Half Dead" isn't what anybody would consider a "typical" Dworkin screed so it had to be real.

More depressing is the LaBute piece, "Slave to the Office," which somehow aims to make you feel faint pangs of pity for an office bully halfway between asshole and pathetic. Boy has LaBute painted himself into a corner at this point. He has such ease as a stylist, but for what? Cheap effects in the service of devious targets. Still, I keep going back to his stories and plays. It must be nostalgie de la boue.

Palahniuk, at least, achieves a certain 21st-century Freaks-ishness in "Mister Elegant." The take on ideas of normalcy and physical appearance may be only Twilight Zone–deep, but I found the piece's black humor rather effective. It somehow reminded me a bit of what I like in Judy Budnitz's stories. Her work is less anchored in a certain type of hyper-reality, but she also captures the grotesqueries of life.

So there you go: Vice's fiction issue. It's free, pick it up.

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Squeeeeal like a pig!

Coming out of a rock show half-deaf, I'm familiar with; but emerging half-blind as well, that was new. Not only did Clockcleaner play loud at Cake Shop on Friday night, but they also turned off the stage lights and turned on a couple of blue strobes. My ears! My eyes! It was sensory-

Coming out of a rock show half-deaf, I'm familiar with; but emerging half-blind as well, that was new. Not only did Clockcleaner play loud at Cake Shop on Friday night, but they also turned off the stage lights and turned on a couple of blue strobes. My ears! My eyes! It was sensory-overload agony, and I was in ecstasy. And I'm pretty sure it wasn't all because of some nostalgia trip either: Sure, the Philly trio sounds like it's listened to the entire AmRep catalogue back to front, but it's already developed a live power that's all its own. And bassist Karen has a sturdy, no-nonsense presence that reminds me of the glory days of Kim Deal (not a coincidence I guess, since I hear Clockcleaner did a Breeders cover at its WFMU appearance earlier this month.)

The band has recentish MP3s on its website, so here's a couple of older tracks, from its 2004 debut EP The Hassler:

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

What the jury heard

Updates have been woefully rare since the end of November, as that period has been uncharacteristically busy. At least I can now reveal the main reason the Dilettante got so little attention: I was a member of the advisory review panel for the New York State Music Fund, which has just announced a new batch of grants. You can see discover where they went there.

In short, the NYSMF was redistributing money from fines paid by the major record labels, which had been sued by State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer for payola. Being a panelist for the Fund was extraordinarily demanding but also extraordinarily exciting. I can safely say I learned more about music-related institutions in New York State in the past couple of months than in the past couple of years. And soon, we'll all get to hear what that windfall help produce.

In short, the NYSMF was redistributing money from fines paid by the major record labels, which had been sued by State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer for payola. Being a panelist for the Fund was extraordinarily demanding but also extraordinarily exciting. I can safely say I learned more about music-related institutions in New York State in the past couple of months than in the past couple of years. And soon, we'll all get to hear what that windfall help produce.

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

Help raise the freak flag

A group of New York theater gals led by playwright Kate Moira Ryan, director Leigh Silverman and writer/actor (and New York Theater Workshop associate artistic director) Linda Chapman has teamed up with the equally excellent Hourglass Group, whose past productions include a wonderful stage adaptation of Lubitsch's Trouble in Paradise (starring the always fine Nina Hellman).

A group of New York theater gals led by playwright Kate Moira Ryan, director Leigh Silverman and writer/actor (and New York Theater Workshop associate artistic director) Linda Chapman has teamed up with the equally excellent Hourglass Group, whose past productions include a wonderful stage adaptation of Lubitsch's Trouble in Paradise (starring the always fine Nina Hellman).And to what end, you may wonder, already bedazzled by this introductory list of names, slathered with praise like jam on toast ? Well, they want to stage Ann Bannon's pulpy book The Beebo Brinker Chronicles, and they're now doing some fund-raising. The novel is a classic of overheated 1950s paperback lit, as examplified by its front-cover blurb: "Lost, lonely, boyishly appealing—this is Beebo Brinker—who never really knew what she wanted—until she came to Greenwich Village and found the love that smoulders in the shadows of the twilight world." Come on, what would you rather see on stage, this or the latest hairball coughed up by Richard Greenberg?

So giddyup and fork out some $$$. After all, it's the time of the year when we're meant to be generous. You can donate through their new website, or check in with the Hourglass Group.

Saturday, December 09, 2006

It's astounding, time is fleeting…

…madness takes its toll. And boy, did it!

Based on a glowing recommendation from my colleague Adam Feldman, I dropped by Joe's Pub Friday evening to check out Leslie Kritzer Is Patti LuPone at Les Mouches, an unwieldy title that turned out to hide a dynamite show, as Ed Sullivan would put it.

The basic concept is that Kritzer reproduces Patti LuPone's last set at Les Mouches, a Chelsea boîte where Patti held a Saturday residency for 30 weeks in 1980—performing right after appearing in Evita on Broadway. Oddly, this is the second show I've seen in the past couple of months where a performer has turned a nominal homage into a memorable, completely original evening. And Kritzer had set herself a challenge even bigger than the one Terese Genecco faced in her tribute to Frances Faye, because Genecco dealt with Faye in general, telling the audience about her subject's life for instance; Kritzer, however, is reproducing a particular set's song list and banter, making it trickier to both avoid simply mimicking her model and put her own stamp on the material. That she delivers the most high-octane performance I've seen in ages must be credited to her powerhouse voice, interpretative chops and deadly comic timing—and those are her own and nobody else's.

Making her grand entrance with "She's a Latin from Manhattan," Kritzer hilariously emphasized LuPone's tendency to slur lyrics into complete unintelligibility, but she dropped the strict emulation quickly and somehow managed to appropriate songs indelibly associated with Her Royal Pattiness, like "Meadowlark" and "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina."

A side result of listening to this recreation is that I was once again struck by the porous barriers between genres in 1980. Patti was doing "Love for Sale" but also "Superman" and "Because the Night," rock songs that were newish at the time—compare this to contemporary cabaret artists who pat themselves on the back for dipping into the back catalogs of Randy Newman, Laura Nyro or Joni Mitchell. And let's not forget the time-warp experience of "Heaven Is a Disco," a 1977 song by Paul Jabara—author of the immortal "Last Dance" and "No More Tears (Enough Is Enough)"—that suddenly turned Joe's into Studio 54.

After looking her up, I realized that I had actually seen Kritzer before—in a 2000 revival of Godspell at the Theater at St Peter's that also starred then-unknowns Barrett Foa and Capathia Jenkins. I can't honestly say I had singled out Kritzer at the time, essentially because the entire cast of that zippy production was surprisingly good.

And while we're on the subject of Patti LuPone, I may have to check out Jet Blue's fares: She and Audra McDonald are starring in Brecht and Weill's Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny at Los Angeles Opera in February/March; even better, the production is directed by John Doyle, who excellently staged Sweeney Todd on Broadway last year (and, granted, is less successful in the current revival of Company).

Based on a glowing recommendation from my colleague Adam Feldman, I dropped by Joe's Pub Friday evening to check out Leslie Kritzer Is Patti LuPone at Les Mouches, an unwieldy title that turned out to hide a dynamite show, as Ed Sullivan would put it.

The basic concept is that Kritzer reproduces Patti LuPone's last set at Les Mouches, a Chelsea boîte where Patti held a Saturday residency for 30 weeks in 1980—performing right after appearing in Evita on Broadway. Oddly, this is the second show I've seen in the past couple of months where a performer has turned a nominal homage into a memorable, completely original evening. And Kritzer had set herself a challenge even bigger than the one Terese Genecco faced in her tribute to Frances Faye, because Genecco dealt with Faye in general, telling the audience about her subject's life for instance; Kritzer, however, is reproducing a particular set's song list and banter, making it trickier to both avoid simply mimicking her model and put her own stamp on the material. That she delivers the most high-octane performance I've seen in ages must be credited to her powerhouse voice, interpretative chops and deadly comic timing—and those are her own and nobody else's.

Making her grand entrance with "She's a Latin from Manhattan," Kritzer hilariously emphasized LuPone's tendency to slur lyrics into complete unintelligibility, but she dropped the strict emulation quickly and somehow managed to appropriate songs indelibly associated with Her Royal Pattiness, like "Meadowlark" and "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina."

A side result of listening to this recreation is that I was once again struck by the porous barriers between genres in 1980. Patti was doing "Love for Sale" but also "Superman" and "Because the Night," rock songs that were newish at the time—compare this to contemporary cabaret artists who pat themselves on the back for dipping into the back catalogs of Randy Newman, Laura Nyro or Joni Mitchell. And let's not forget the time-warp experience of "Heaven Is a Disco," a 1977 song by Paul Jabara—author of the immortal "Last Dance" and "No More Tears (Enough Is Enough)"—that suddenly turned Joe's into Studio 54.

After looking her up, I realized that I had actually seen Kritzer before—in a 2000 revival of Godspell at the Theater at St Peter's that also starred then-unknowns Barrett Foa and Capathia Jenkins. I can't honestly say I had singled out Kritzer at the time, essentially because the entire cast of that zippy production was surprisingly good.

And while we're on the subject of Patti LuPone, I may have to check out Jet Blue's fares: She and Audra McDonald are starring in Brecht and Weill's Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny at Los Angeles Opera in February/March; even better, the production is directed by John Doyle, who excellently staged Sweeney Todd on Broadway last year (and, granted, is less successful in the current revival of Company).

Friday, December 08, 2006

The Rural Juror

The "rural juror" joke alone would be enough to make me eat crow, but there's been plenty more of that ilk on 30 Rock, the sitcom I once described as a turkey. A hasty judgment, obviously, since against all odds (1. Tina Fey as an actress, 2. Tracy Morgan, 3. Tina Fey as an actress) the show has been steadily improving and now qualifies as a weekly delight. Okay, so I was wrong—at least give me some brownie points for admitting the error of my ways.

And while we're in the realm of "things I never thought I'd say": The Met Opera is exciting! The recent announcement that it's going to present Philip Glass's 1982 Satyagraha in 2008 may have raised my pulse by a couple of ticks on its own, but what really makes me count the weeks is the news that it'll be staged by Phelim McDermott and Julian Crouch, of Britain's Improbable company. McDermott and Crouch co-directed Shockheaded Peter, a wonderful, innovative piece of musical theater which, under the pretense of being a kids' show (its first NYC production was at the New Victory), brilliantly exposed the stuff that nightmares are made of. Their Hanging Man at BAM in 2003 wasn't too shabby either.

Now if we somehow could get Tina Fey and Peter Gelb to meet…

And while we're in the realm of "things I never thought I'd say": The Met Opera is exciting! The recent announcement that it's going to present Philip Glass's 1982 Satyagraha in 2008 may have raised my pulse by a couple of ticks on its own, but what really makes me count the weeks is the news that it'll be staged by Phelim McDermott and Julian Crouch, of Britain's Improbable company. McDermott and Crouch co-directed Shockheaded Peter, a wonderful, innovative piece of musical theater which, under the pretense of being a kids' show (its first NYC production was at the New Victory), brilliantly exposed the stuff that nightmares are made of. Their Hanging Man at BAM in 2003 wasn't too shabby either.

Now if we somehow could get Tina Fey and Peter Gelb to meet…

Sunday, December 03, 2006

Charity, Scandi style

Just because they're giving it away doesn't mean it's bad!

Just because they're giving it away doesn't mean it's bad!The Swedish label Sudd, operating out of Goteborg, has had the brilliant idea of doing an MP3 advent calendar: They're offering a new track every day of December until Christmas eve. Today, for instance, is Sophie Rimheden and Sofia Talvik's lovely techno-pop number "Xmas on the Dance Floor" (which made it to my top ten of last year, despite usually having very little patience for holiday songs).

Elsewhere in Sweden, Stockholm duo Small Feral Token (pictured) has put up 17 of its songs for free download.

December is the best time of the year to enjoy Swedish deliciousness!!!

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Heavy rotation

Cobra Killer is the Carl Stalling of gonzo tech-punk. Few bands so habitually confound expectations and so cleverly weave strands of disparate musics into consistent albums.

Cobra Killer is the Carl Stalling of gonzo tech-punk. Few bands so habitually confound expectations and so cleverly weave strands of disparate musics into consistent albums.As I wrote in this week's Time Out (link not up yet for some reason), Cobra Killer is scheduled to hit Tonic tomorrow evening. Gina V. D'Orio and Annika Line Trost are off the charts (to quote Dina Martina) live, not to mention among the nuttiest interviews I've ever done, even if it was by email. And since they cancelled their past two NYC shows at the last minute, all digits are crossed for this one.

While Cobra Killer's often been compared to Peaches because they all are women who at one point relied on basic electronics, the comparison treads water, especially now that Peaches' radical rep solely rests on her lyrics, as she's considerably streamlined and beefed up her sound, and the days of triggering her sampler on stage have given way to touring with a full band (more later on last week's show at Irving Plaza, if I can find some time). Cobra Killer, on the other hand, confounds pretty much all the expectations you could have from people making music, down to their relationship with their instruments (they basically shun them live). What they play is deceptively simple but on stage they take it so far as to be in a league of their own.

For now, here are a few tunes to enjoy while counting down the minutes to the show.

"H-Man-A Psychocat" and "Loaders in Octobers" are pulled from CK's sophomore album, 2002's The Third Armpit. Released on the Australian label Valve and relatively hard to find, it marked the band's transition from saturated digital-hardcore ADD to cleaner swinging Berlin.

Plus! Special extra-super-duper geek-out bonuses with…side projects! Because Trost and D'Orio just can't stop the music, and I can't stop hunting it down. D'Orio has released the solo CD Sailor Songs on Australia's excellent label Dual Plover; minimalist half-booty musicalizations of American high-school dramas with Patric "ec8or" Catani under the name A*Class; and Bass Girl, a collaboration with Like a Tim, from which "I Only Have Eyes for You" is pulled. Meanwhile, Trost has released two solo CDs; "I Was Wrong" is on the latest one, Trust Me (2006).

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Oh hell…

Double bummer reading the Times yesterday: Betty Comden and Anita O'Day died on Thursday.

Double bummer reading the Times yesterday: Betty Comden and Anita O'Day died on Thursday.Comden and her writing partner Adolph Green were my favorites in the world of stage and film musicals. Their lyrics could put high-brow references in a decidedly low-brow context, or turn the banality of everyday life into elegant melancholy—qualities that are exactly reflected in their scripts for On the Town and The Band Wagon. Comden and Green were open to the world around them, and connected to it with an uncommon relish that gave their work a unique verve and humor.

Below you can download their own versions of a pair of songs from one of their lesser-known efforts, Two on the Aisle, a 1951 stage vehicle for Dolores Gray and Bert Lahr.

As for Anita O'Day, she was my favorite jazz singer—and among my top five favorite singers, period—though I discovered her not through jazz but through show tunes. More specifically, her rendition of "Who Cares?," from the 1931 Gershwin musical Of Thee I Sing. O'Day's voice had a smoky texture not unlike Dusty Springfield's (another entry in the all-time list). There are many things to praise about her but my favorite aspect of her performing style was the way she could sing very, very fast with no loss in clarity or interpretative subtlety whatsoever. Her 1959 album Anita O'Day Swings Cole Porter with Billy May, of which "Just One of Those Things" is the opening track, is packed with breakneck takes on Porter classics. As for the details of her life, the title of her autobiography, High Times Hard Times, pretty much says it all.

Anita O'Day: "Just One of Those Things"

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Does anybody remember laughter?

I've said it before but there's new evidence that we're in the middle of a rather good season for comedy. The new production of Rossini's Il Barbiere di Seviglia at the Met is a heap of giddy fun, though this has little to do with director Bartlett Sher: The man should count his blessings for scoring a dream cast that's like a bunch of homing pigeons with an unerring sense of their comedic (and vocal) home. The three leads, in particular—Peter Mattei (Figaro), Juan Diego Floréz (Count Almaviva) and Diana Damrau (Rosina)—could not have been better suited to their roles; in fact, they could have been planted on a traffic island in the middle of Broadway at rush hour and they'd still would have killed.

I've said it before but there's new evidence that we're in the middle of a rather good season for comedy. The new production of Rossini's Il Barbiere di Seviglia at the Met is a heap of giddy fun, though this has little to do with director Bartlett Sher: The man should count his blessings for scoring a dream cast that's like a bunch of homing pigeons with an unerring sense of their comedic (and vocal) home. The three leads, in particular—Peter Mattei (Figaro), Juan Diego Floréz (Count Almaviva) and Diana Damrau (Rosina)—could not have been better suited to their roles; in fact, they could have been planted on a traffic island in the middle of Broadway at rush hour and they'd still would have killed.Sher's own contributions to the comedy unfurling on stage were modest: extending the stage to a runaway going around and in front of the orchestra pit; the hapless silent servant; the giant anvil that falls down and squashes a cart at the end of Act I—a bit of literal illustration of the lyrics that was so OTT that it worked for me. Funny biz, but really, how do you improve on genius cartoon director Tex Avery when it comes to dropping anvils? As for the rest, Sher ably moved the cast about the stage and wisely stayed out of its way: Barbiere is naturally packed with action and it'd take someone with actual ideas—like Chuck Jones, the director of Rabbit of Seville—to make it even zippier. (For a director who actually makes a funny show funnier, try to catch Jonathan Miller's production of The Mikado, set in the 1920s, at City Opera.)

Even the business with the several free-standing, movable doors dot the set seemed to function in spite of Sher's intentions. When I first saw them, I thought he was making a visual reference to the comedy of slammed doors of Feydeau, but reading his notes in the program at intermission, I discovered he intended them to suggest a sense of claustrophobia. Right, the dark, edgy stuff that must be injected in comedies lest the audience think it's paying $275 for fluff! At least he completely failed in that respect.

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Madame la Présidente?

Psyched!!! In a primary, the members of the French Socialist Party chose Ségolène Royal to carry their colors in next year's election. (Fine, I fess up: I was a due-paying member for years but decided not to renew after the banlieue riots of 2005, and so didn't vote in the primary.) Truly, no other choice was possible since the other two candidates—super-technocratic Dominique Strauss-Kahn and perennial arriviste Laurent Fabius—could never have won against the likely candidate of the right, Nicolas Sarkozy. Ségo hatas had predicted that she wouldn't get a majority and that there would have to be a second round, but she sailed through with 60 percent of the vote.

Psyched!!! In a primary, the members of the French Socialist Party chose Ségolène Royal to carry their colors in next year's election. (Fine, I fess up: I was a due-paying member for years but decided not to renew after the banlieue riots of 2005, and so didn't vote in the primary.) Truly, no other choice was possible since the other two candidates—super-technocratic Dominique Strauss-Kahn and perennial arriviste Laurent Fabius—could never have won against the likely candidate of the right, Nicolas Sarkozy. Ségo hatas had predicted that she wouldn't get a majority and that there would have to be a second round, but she sailed through with 60 percent of the vote.To me, this means that barring an unforeseen disaster (and maybe with some underhand help from Chirac, who hates Sarko and many think would rather see a Socialist win rather than him), she will become the next French president. French politics are going to be very interesting in the coming months, especially since Ségo can expect some backstabbing from within her own party.

Now we need the non-Socialist left to get its act together and not spew several candidates who may split the vote during the presidential election's first round, the way it happened back in 2002, when it led to far-right scarecrow Jean-Marie Le Pen battling lame-duck Chirac in the second round. Though I suspect that even with the usual suspects threatening to clog the first round again (can't the goddam Trotskyists pack it in already?!), voters may have learned a lesson.

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

From Sweden, with angst

New Yorker Films recently released on DVD two striking Mai Zetterling films which show the Swedish actress to also have been a pioneering director. Loving Couples (1964) interweaves the back stories of three pregnant women who happen to all be in the same hospital at the same time (around the beginning of the 20th century), and also happen to know each other. The gorgeous b&w cinematography—well it can be gorgeous, it's by Ingmar regular Sven Nykvist—reinforces the unblinking sharpness of Zetterling's look at the relations between men and women. (Needless to say, the title is highly ironic.) The movie ends with what looks like a real birth, which I'm sure must have gone over well with 1964 audiences.

But even Loving Couples pales in comparison to The Girls (1968), whose modernity just blew me away. I don't understand why this movie isn't hailed as a prime example of 1960s modernism. Perhaps the DVD will help change that.

The Girls follows a predominently female theater troupe as it tours Lysistrata in Swedish backwater towns and as its leads (Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson and Gunnel Lindblom, no less) express a growing feminist consciousness. But the best thing is that Zetterling goes all Godard on us, playing out her manifesto in a way that seems to imply that traditional filmmaking is a tool of the patriarchy and subverting it is a feminist imperative. And so she plays with the superimposition of sound and image (one preceding or following the other for instance), with fantasy sequences, with chronology, with editing. Plus every shot looks incredible, ready for framing—what an eye Zetterling had! The Girls is a triumph of form and function.

Wrapping up my Swedish week was El Perro del Mar at Joe's Pub. Sarah Assbring (who basically is El Perro del Mar, though she was backed on stage by a few guys) plays intimate pop songs that feel like Brill Building anthems with all the fun sucked out of them. She was stylish but dry dry dry, and her stern demeanor hid lightweight songs.

Émilie Simon, who followed her up on stage, was the exact opposite: a serious experimenter (she studied at Pierre Boulez's IRCAM) under a foofy exterior. Simon's released three popular electronic-based albums in her native France, including the original soundtrack for March of the Penguins. Because her musicians got last-minute visa problem, her New York debut also was her live-solo debut as she accompanied herself on guitar or on piano, with some prerecorded stuff coming out of a laptop perched on a chair. She occasionally shot sideway coy glances at the audience while singing in her girlish voice—all things I usually hate in performers but which she managed to pull off, coming across as endearingly kooky rather than clumsily flirtatious.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Moving to bigger—better?—things

Over the past few days I had the opportunity to re-see Grey Gardens (left) and The Little Dog Laughed, two Broadway shows I'd first caught in their Off incarnations. Both had serious flaws that have been only partly fixed, and both illustrated why seeing a show in a smaller setting tends to be preferable.

Over the past few days I had the opportunity to re-see Grey Gardens (left) and The Little Dog Laughed, two Broadway shows I'd first caught in their Off incarnations. Both had serious flaws that have been only partly fixed, and both illustrated why seeing a show in a smaller setting tends to be preferable.Grey Gardens is based on the Maysles brothers' doc of the same title, which portrays the decrepit life of Edith Bouvier Beale and her daughter, Little Edie, in the early 1970s. The show's second act follows the movie pretty faithfully, with Mary Louise Wilson and Christine Ebersole giving stunning performances as Edith and Little Edie, respectively. The problem is that book writer Doug Wright added a whole new prelude set in 1941 in which we see how the mother-daughter duo (with Ebersole playing Big Edie and Erin Davie playing Little Edie) got that way. But did we really need any insight into how the women of Grey Gardens (the name of their mansion) turned out the way they did? Why this mania to explain everything? Couldn't the show have been a one-act, 90-minute piece set in the 1970s? One of the reasons the movie is so fascinating is that there are suggestions to a past grandeur but the women's eccentricities stand on their own.

While the musical's first act has been tightened up, its pulse rate is still flat. It feels like a drawing-room dramedy, making the second act even more stupendous in comparison: Suddenly, you feel as if you're watching a completely different show, and a much better one at that. And it was even better Off Broadway, where the cozier setting allowed the mix of pathos and ridicule to gel to a highly uncomfortable degree.

As for The Little Dog Laughed, it is still very funny and it feels good to have a genuine comedy on Broadway. Douglas Carter Beane has a way with one-liners and the cast ably delivers them. And yes, Julie White—as a Hollywood agent with her tongue set to stun—is amazing. But this time around she turns it up a smidgen too high, as if she felt she had to fill every nook and cranny of the bigger house. Her performance was absolutely perfect when the show was at Second Stage; now it feels a bit shrill, especially in the first act, and rates only as almost perfect. Still, this is a quibble: Comedic tours de force such as the one White delivers nightly are too rare to be missed.

Monday, November 13, 2006

Stop the presses!

Rumor has it that Madonna is set to record a new track with Agnetha and Frida (the singers from Abba of course. Sheesh, do I need to tell you everything?). Now if this turns out to be true—the reputable source of information known as The Sun broke the story after all—this would be a 124.8 on the Richter scale of popquakes, just below an actual ABBA reunion or Dusty Springfield coming back from the dead for a cryogenic show.

So many urgent questions! Will the three women write the song together? Will it be done for charity, as these projects so often are? What name will the trio use? (Some wags suggest MABBA, but MAA would be more accurate since Benny and Björn aren't likely to be involved.) Will the famously reclusive Agnetha fly to England to record or will she make the others fly to her in Sweden?

Oh, I need to go to bed with a wet towel on my burning forehead.

So many urgent questions! Will the three women write the song together? Will it be done for charity, as these projects so often are? What name will the trio use? (Some wags suggest MABBA, but MAA would be more accurate since Benny and Björn aren't likely to be involved.) Will the famously reclusive Agnetha fly to England to record or will she make the others fly to her in Sweden?

Oh, I need to go to bed with a wet towel on my burning forehead.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Lepideptora Majora

Anthony Minghella's never really done it for me as a film director because he never digs very far beneath the surface and seems to be adverse to actual perversity (e.g., The Talented Mr. Ripley, Cold Mountain), but his Madama Butterfly at the Met is stunning.

Anthony Minghella's never really done it for me as a film director because he never digs very far beneath the surface and seems to be adverse to actual perversity (e.g., The Talented Mr. Ripley, Cold Mountain), but his Madama Butterfly at the Met is stunning.Minghella doesn't offer any new reading of the tragic story of Cio-Cio-San, the 15-year-old Japanese geisha who's seduced and abandoned by US Navy lieutenant Pinkerton, then commits suicide three years later, after Pinkerton comes back to Japan and threatens to take their son away from her. So no, Minghella doesn't interpret, he illustrates—but what illustrations! Stealing his blues and reds from the palette of Robert "If Only I Had a Heart" Wilson, Minghella unfurls one stunning visual composition after another, and salvages Madama Butterfly from the kitsch heap it so often ends up in. Butterfly's death has to be the single most striking visual I've seen all year (you only have three more opportunities to see it this season) and the use of a bunraku puppet for her son is heartbreakingly efficient. I cannot fathom why there's been so much hostility for that concept from some opera corners.

But the beauty of what's on stage never gets in the way of actual emotion, even if I do have a bone to pick with the decision to play Cio-Cio-San like a shaky, timid, virginal girl in the first act. She may be only 15, but she's also a geisha. I'd have loved to see Cristina Gallardo-Domâs at least suggest a smidgen of flirtatiousness when she meets Pinkerton. Her gradual crushing in Acts II and III would still work: Just because she's a ho doesn't mean Butterfly can't develop real feelings for her new man, as anybody familiar with Nights of Cabiria, Sweet Charity, Irma La Douce and the R&B canon will know.

If this production is indicative of the Met's new direction under Peter Gelb, count me in. Even the playbill looked better, as if the Met had finally discovered there's something called desktop publishing out there; and it wasn't all cosmetic, the content was spiffier as well. For now Gelb's strategy seems to work at least in terms of creating a new sense of urgency and relevance. Not only were there actual scalpers outside, but the crowd did look a little with it. Plus I was sitting across the aisle from Patti Smith, who may not be young and with it but still was the coolest person in the room.

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Reno 911!

Over the past few years, Jean Reno has replaced Gérard Depardieu as the embodiment of a certain kind of French maleness in Hollywood, so much so that in the new DreamWorks/Aardman feature, Flushed Away, he voices a character named Le Frog.

When Hollywood needs a Gaul, Reno dutifully punches in his time card—except that unlike Depardieu and earlier imports such as Charles Boyer, his characters aren't sexual. I think it all started in ’95 with the horrid Meg Ryan/Kevin Kline vehicle French Kiss, in which Reno played an inspector. Then he was a French secret agent in Godzilla, a French cop in The Pink Panther and The Da Vinci Code, a French Airforce pilot in Flyboys. Lots of manly-man stuff—albeit sometimes of the bumbling kind—but not much traditional sex-ay action. Interestingly, the disappearance of the sexy French stud from American movies (except for Olivier Martinez in Unfaithful I guess) has corresponded with the years in which France has become the symbol of fey European weakness for a lot of red staters Gone are the days of Le Shaggeur, welcome to Le Frog.

When Hollywood needs a Gaul, Reno dutifully punches in his time card—except that unlike Depardieu and earlier imports such as Charles Boyer, his characters aren't sexual. I think it all started in ’95 with the horrid Meg Ryan/Kevin Kline vehicle French Kiss, in which Reno played an inspector. Then he was a French secret agent in Godzilla, a French cop in The Pink Panther and The Da Vinci Code, a French Airforce pilot in Flyboys. Lots of manly-man stuff—albeit sometimes of the bumbling kind—but not much traditional sex-ay action. Interestingly, the disappearance of the sexy French stud from American movies (except for Olivier Martinez in Unfaithful I guess) has corresponded with the years in which France has become the symbol of fey European weakness for a lot of red staters Gone are the days of Le Shaggeur, welcome to Le Frog.

This year's Goncourt

The Goncourt, France's biggest literary prize, has just been attributed to Jonathan Littell's Les Bienveillantes. I've only reached page 250 (out of 900) so will refrain from commenting for now, but a small detail buried at the end of a Libération article about Littell struck me: Apparently, the American-born author, who's lived in France and wrote his novel directly in French, was turned down for French nationality twice. That decision strikes me as ill-considered and embarrassing (I'd be curious to know on what grounds Littell's request was turned down), especially since I myself got dual French-American citizenship a few weeks ago. But of course it's only part of France's generally awkward, to put it politely, attitude toward immigration. If the Yale-educated son of a best-selling writer (Robert Littell) gets turned down for French citizenship, just imagine the obstacles put up in front of immigrants from Mali or Afghanistan. What most impressed me when I took the oath at a Brooklyn courthouse was the sheer diversity of the 400 or so people in the room with me. Of course this doesn't mean American immigration policy is so hot right now—the country is building a wall on its border with Mexico after all—but it strikes me as still more accomodating than what passes for immigration policy in France.

The Goncourt, France's biggest literary prize, has just been attributed to Jonathan Littell's Les Bienveillantes. I've only reached page 250 (out of 900) so will refrain from commenting for now, but a small detail buried at the end of a Libération article about Littell struck me: Apparently, the American-born author, who's lived in France and wrote his novel directly in French, was turned down for French nationality twice. That decision strikes me as ill-considered and embarrassing (I'd be curious to know on what grounds Littell's request was turned down), especially since I myself got dual French-American citizenship a few weeks ago. But of course it's only part of France's generally awkward, to put it politely, attitude toward immigration. If the Yale-educated son of a best-selling writer (Robert Littell) gets turned down for French citizenship, just imagine the obstacles put up in front of immigrants from Mali or Afghanistan. What most impressed me when I took the oath at a Brooklyn courthouse was the sheer diversity of the 400 or so people in the room with me. Of course this doesn't mean American immigration policy is so hot right now—the country is building a wall on its border with Mexico after all—but it strikes me as still more accomodating than what passes for immigration policy in France.

Saturday, November 04, 2006

Last remarks on the French trip, I swear!

This didn't feel like it belonged in the Quartett post, but there were actually other things happening in France. (I know, I know…)

• Oddball stage adaptations: There's now Bagdad Café: The Musical, adapted by director Percy Adlon from his own inexplicably overrated 1987 film. But perhaps you'd prefer Dolores Claiborne, a play based on Stephen King's novel of the same name, and starring comedian Michèle Bernier?

• Also live in the flesh in Paris: Hollywood's favorite Hire-a-Frog Jean Reno, Alain Resnais regular Pierre Arditi, diaphanous blonde Isabelle Carré, snooty brainiac Jeanne Balibar, dryly funny Catherine Frot.

• But wait, there's better: Dita von Teese was making her debut at the Crazy Horse Saloon! Like the Lido, the Crazy Horse Saloon is a Paris-style cabaret, meaning it doesn't involve Gershwin or Porter but topless ladies cavorting on a small stage while the audience dines at surrounding tables—kinda like Cristal Connors's numbers in Showgirls but, you know, with French boobs.

• What's up with Harlan Coben?!? French libraries stack his books in huge piles and every other person on the metro seemed to be reading him. Not only that, but Coben's thriller Tell No One was turned into one of the fall's big French films, Guillaume Canet's Ne le dis à personne. Actually, someone should look into how American or English thrillers often are adapted into completely different but very good French movies: Ruth Rendell's A Judgment in Stone became Claude Chabrol's The Ceremony and Jim Thompson had the honors twice: Pop. 1280 became Bertrand Tavernier's Coup de Torchon (transposed to colonial Africa) and A Hell of a Woman became Alain Corneau's Série Noire.

• And speaking of books: On my next-to-last day I gave in to curiosity and purchased Jonathan Litell's mega-hyped doorstopper, Les bienveillantes, a book mentioned as a candidate to every French literary prize. Even better, I bought it at a supermarket in the Corsican boondocks, putting it in my basket between the chestnut pasta and the yogurts. For indeed many French supermarkets carry books and CDs. Just imagine being able to buy a 900-page novel narrated by a gay SS officer at Key Food…

• Oddball stage adaptations: There's now Bagdad Café: The Musical, adapted by director Percy Adlon from his own inexplicably overrated 1987 film. But perhaps you'd prefer Dolores Claiborne, a play based on Stephen King's novel of the same name, and starring comedian Michèle Bernier?

• Also live in the flesh in Paris: Hollywood's favorite Hire-a-Frog Jean Reno, Alain Resnais regular Pierre Arditi, diaphanous blonde Isabelle Carré, snooty brainiac Jeanne Balibar, dryly funny Catherine Frot.

• But wait, there's better: Dita von Teese was making her debut at the Crazy Horse Saloon! Like the Lido, the Crazy Horse Saloon is a Paris-style cabaret, meaning it doesn't involve Gershwin or Porter but topless ladies cavorting on a small stage while the audience dines at surrounding tables—kinda like Cristal Connors's numbers in Showgirls but, you know, with French boobs.

• What's up with Harlan Coben?!? French libraries stack his books in huge piles and every other person on the metro seemed to be reading him. Not only that, but Coben's thriller Tell No One was turned into one of the fall's big French films, Guillaume Canet's Ne le dis à personne. Actually, someone should look into how American or English thrillers often are adapted into completely different but very good French movies: Ruth Rendell's A Judgment in Stone became Claude Chabrol's The Ceremony and Jim Thompson had the honors twice: Pop. 1280 became Bertrand Tavernier's Coup de Torchon (transposed to colonial Africa) and A Hell of a Woman became Alain Corneau's Série Noire.

• And speaking of books: On my next-to-last day I gave in to curiosity and purchased Jonathan Litell's mega-hyped doorstopper, Les bienveillantes, a book mentioned as a candidate to every French literary prize. Even better, I bought it at a supermarket in the Corsican boondocks, putting it in my basket between the chestnut pasta and the yogurts. For indeed many French supermarkets carry books and CDs. Just imagine being able to buy a 900-page novel narrated by a gay SS officer at Key Food…

Crawling back into dilettantism

Yikes, vacation sure can take its toll on a blog, though it's also great to leave the web alone for a while. A few thoughts to wrap up the French trip, which was lighter on the gulcher than usual (though I'd certainly include watching Over the Hedge, which includes a brilliant voice-over performance by Steve Carell, on video).

Yikes, vacation sure can take its toll on a blog, though it's also great to leave the web alone for a while. A few thoughts to wrap up the French trip, which was lighter on the gulcher than usual (though I'd certainly include watching Over the Hedge, which includes a brilliant voice-over performance by Steve Carell, on video).I suppose the main event was seeing Heiner Müller's Quartett, which I've alluded to before. The text is based on Laclos' Liaisons dangereuses, which Müller has boiled down to its two key characters, Valmont and Merteuil, and to a dozen incredibly dense pages. I'd love to see it again in a production emphatically not by Robert Wilson, whose formula just feels tired and mercenary at this point—mercenary because based on the past five-six shows by him I've seen, he now applies the same predictable boilerplate tricks to whatever he's meant to stage at one of the many international houses of culture that inexplicably keep on hiring him. In the case of this Quartett, Wilson incorporated elements from two of his own previous stagings. From the 1988 New York production, for instance, we seemed to inherit the three extra characters—including an old man—and a prologue of a sort in which the actors seat at a banquet table.

While Wilson had Lucinda Childs as Merteuil back then, we had Isabelle Huppert, who was the show's main draw. The command she had over the technical aspects of her performance was astonishing, something that was obvious from her first line, which she repeated over and over with barely perceptible variations in speed and pitch, incongruously—and somehow convincingly—sounding like a spoken version of a Philip Glass piece. It's hard to talk about anything that's not purely technical when referring to actors in a Wilson piece anyway, because to him they are nothing more than elements in his visual compositions, no more or less important than the lighting, costumes or set. No wonder he makes them move slowly and adopt dramatically geometric gestures: The only obviously human component he allows them is speech (and in this case not even to all of them—of the five people onstage in this Quartett, three remain silent). In his notes on the show, Wilson explains that "en 35 ou 38 ans de travail, je n'ai pas une seule fois dit à un comédien ce qu'il devait penser en termes de texte, de sentiment, d'émotion." ("In a 35- or 38-year career, I've never once told an actor what he should think in terms of text, feeling, emotion.")

I don't actually have a problem with that approach, except that to make an impact, you need to deliver superb visuals and topnotch sound design. Alas, Wilson's well seems to have gone dry: At times Quartett felt dated, at others slightly ridiculous (and let's charitably ignore the attempts at humor). I'd be curious to see how long Wilson can continue to coast on two blue spotlights and three red frocks.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Briefs from France

No time to post in Paris as I was busy rediscovering the city on foot (biggest change: the enormous amount of people on bicycles and the effort spent on building new bike paths), spending hours reading the paper in cafés, talking politics with friends (go Ségolène!) and going to the movies. A quick rundown:

- Christophe Honoré's Dans Paris, greeted by very positive reviews, including constant positive nods to the way Honoré honors the New Wave. And he really shoves it down our throats: a direct visual reference to Truffaut's Domicile Conjugal here, a female character named Anna there, and especially Louis Garrel's character, a sub-Jean-Pierre Léaud who didn't get the memo about how Antoine Doinel is meant to remain endearing even when he's irritating. The scene in which Romain Duris and Joana Preiss sing to each other on the phone is really moving, however, a successful Demy pastiche. But the movie tries too hard to be quirky, to be touching, to simply be. Add an awful jazz-lite score and painfully ugly cinematography, and you're left with a piece that does not bode well for French auteur cinema.

- Equally disappointing in a completely different way is Rachid Bouchareb's Indigènes, which won its four lead actors an interpretation prize in Cannes. The movie is about men from the French colonies of North Africa fighting in the French army in 1944-45, and a typical example of how meaning well does not often translate into making good. The actors are indeed excellent, though there's a credibility gap as wide as the Grand Canyon at the center of the movie: Jamel Debbouze has a lame right arm and there's no way a man with only one functional arm would have been accepted in the army, and he certainly would not have been sent to battle with a rifle. To have Debbouze in the part does not make sense, and his handicap is never addressed in the film. Insane! From there on I could not take the movie as seriously as it deserves to be taken.

- two Frenchy-French-French comedies: Eric Rochant's L'école pour tous and, er, some no-name director's Poltergay. Both are ripe for American remakes, though only the former is likely to remain the better version. In L'école pour tous, a banlieue dude poses as a French teacher in a middle school smack in the middle of an at-risk neighborhood in order to evade the police. Various shenanigans and hilarity ensues. The best part of the movie is that the main character does not really improve at the end and does not miraculously become a brilliant teacher. The second best part is director Noémie Lvovsky stealing every scene she's in as a flamboyant fellow teacher. Poltergay benefits from a brilliant title and premise (in addition to Clovis Cornillac's pecs, wasp's waist and excellent comic timing): a couple moves into a house haunted by the ghosts of five gay men who died in a disco fire in 1979. Only other men can see them. Genius! The execution does not always follow but there's nothing a team of Hollywood rent-a-hacks couldn't fix.

- Les honneurs de la guerre, a 1960 movie set in 1945 and scripted by future director Jean-Charles Tacchella. No music, very odd mood for this UFO of a film in which the French villagers are shown as pretty deluded and pathetic, especially the eleventh-hour resistants.

As a side note, going to the movies in Paris is an exquisite pleasure: The screening conditions are generally nice (and often superb) and the silence among the audience nearly absolute. None of that constant bovine munching that accompanies movies in the US, and which I am completely fed up with.

Hey, time for Desperate Housewives dubbed in French! Next post: Heiner Müller's Quartett.

- Christophe Honoré's Dans Paris, greeted by very positive reviews, including constant positive nods to the way Honoré honors the New Wave. And he really shoves it down our throats: a direct visual reference to Truffaut's Domicile Conjugal here, a female character named Anna there, and especially Louis Garrel's character, a sub-Jean-Pierre Léaud who didn't get the memo about how Antoine Doinel is meant to remain endearing even when he's irritating. The scene in which Romain Duris and Joana Preiss sing to each other on the phone is really moving, however, a successful Demy pastiche. But the movie tries too hard to be quirky, to be touching, to simply be. Add an awful jazz-lite score and painfully ugly cinematography, and you're left with a piece that does not bode well for French auteur cinema.

- Equally disappointing in a completely different way is Rachid Bouchareb's Indigènes, which won its four lead actors an interpretation prize in Cannes. The movie is about men from the French colonies of North Africa fighting in the French army in 1944-45, and a typical example of how meaning well does not often translate into making good. The actors are indeed excellent, though there's a credibility gap as wide as the Grand Canyon at the center of the movie: Jamel Debbouze has a lame right arm and there's no way a man with only one functional arm would have been accepted in the army, and he certainly would not have been sent to battle with a rifle. To have Debbouze in the part does not make sense, and his handicap is never addressed in the film. Insane! From there on I could not take the movie as seriously as it deserves to be taken.

- two Frenchy-French-French comedies: Eric Rochant's L'école pour tous and, er, some no-name director's Poltergay. Both are ripe for American remakes, though only the former is likely to remain the better version. In L'école pour tous, a banlieue dude poses as a French teacher in a middle school smack in the middle of an at-risk neighborhood in order to evade the police. Various shenanigans and hilarity ensues. The best part of the movie is that the main character does not really improve at the end and does not miraculously become a brilliant teacher. The second best part is director Noémie Lvovsky stealing every scene she's in as a flamboyant fellow teacher. Poltergay benefits from a brilliant title and premise (in addition to Clovis Cornillac's pecs, wasp's waist and excellent comic timing): a couple moves into a house haunted by the ghosts of five gay men who died in a disco fire in 1979. Only other men can see them. Genius! The execution does not always follow but there's nothing a team of Hollywood rent-a-hacks couldn't fix.

- Les honneurs de la guerre, a 1960 movie set in 1945 and scripted by future director Jean-Charles Tacchella. No music, very odd mood for this UFO of a film in which the French villagers are shown as pretty deluded and pathetic, especially the eleventh-hour resistants.

As a side note, going to the movies in Paris is an exquisite pleasure: The screening conditions are generally nice (and often superb) and the silence among the audience nearly absolute. None of that constant bovine munching that accompanies movies in the US, and which I am completely fed up with.

Hey, time for Desperate Housewives dubbed in French! Next post: Heiner Müller's Quartett.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Solar systems

I'm swamped with work before going on vacation so this will just be a brief plug for two recent Time Out reviews:

I'm swamped with work before going on vacation so this will just be a brief plug for two recent Time Out reviews:• the new Sofie von Otter CD, dedicated to the music of Benny Andersson. I wish I had liked it more since her cover of Abba's "Like an Angel Passing Through My Room" was a highlight of her collaboration with Elvis Costello, For the Stars. Still, it's nice to hear a song from Benny's underrated album Klinga Mina Klockor. Coincidentally I finally saw Mamma Mia! the same week I wrote this review. It was weird to hear all those Abba songs in a different context, i.e. to have them work as devices serving a narrative, and the show's relentlessly bright aesthetics can be tiresome, but Carolee Carmello does a great job as the mother, particularly when she wrings every last drop of outsize tragedy from "The Winner Takes It All."

• the new Solar Anus anthology, which collects this Japanese band's entire recorded output. Psych bands are jam bands for the hipster set and they tend to annoy me after a while—it probably would help if I smoked pot—but this one is relentlessly nuts.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Isabelle vs. Isabelle

A few days after blogging about the two Isabelles (Huppert, left, and Adjani) being on the Parisian stage at the same time—but certainly not the same place—I coincidentally came across a funny article exploring the very same thing. In a Nouvel Observateur piece titled "La guerre des Isabelle" ("the Isabelles War"), Marie-Elisabeth Rouchy details the actresses' rivalry, which goes back to that Brontë sisters movie they made with André Téchiné back in 1979, when their respective agents would time their screen time to make sure one didn't get more than the other. Adjani recalls that Téchiné didn't want them to wear makeup but that they always tried to sneak some on while he wasn't looking so one wouldn't look plainer than the other. (The third sister was played by the wonderful Marie-France Pisier, but you don't see her get into feuds with anybody.)

A few days after blogging about the two Isabelles (Huppert, left, and Adjani) being on the Parisian stage at the same time—but certainly not the same place—I coincidentally came across a funny article exploring the very same thing. In a Nouvel Observateur piece titled "La guerre des Isabelle" ("the Isabelles War"), Marie-Elisabeth Rouchy details the actresses' rivalry, which goes back to that Brontë sisters movie they made with André Téchiné back in 1979, when their respective agents would time their screen time to make sure one didn't get more than the other. Adjani recalls that Téchiné didn't want them to wear makeup but that they always tried to sneak some on while he wasn't looking so one wouldn't look plainer than the other. (The third sister was played by the wonderful Marie-France Pisier, but you don't see her get into feuds with anybody.)More good stuff from the article for non-francophones:

In the late ’70s, Huppert and Adjani both wanted to star in a film adaptation of Théophile Gaultier's La dame aux camélias (usually known here as Camille). Huppert won that one, but Adjani scored a few years later when she got to do a project they both coveted, the life of Camille Claudel.

Even more deliciously (and that I had totally forgotten about), Huppert starred in Schiller's Maria Stuart in London in 1996—the character Adjani is now playing in Paris, but in Wolfgang Hildsheimer's lesser-known version of Stuart's last moments.

Rouchy also tallies the actresses' Césars (Adjani's four to Huppert's one), respective filmographies (Adjani's 27 movies to Huppert's 76) and media profiles (Adjani's breakup with Jean-Michel Jarre lands her in French celebrity magazines, Huppert gets a retrospective at MoMA and a hardcover book of portraits).

Since of course it's more exciting pick a camp, I unhesitantly join the Huppertists—though it's quite fun to watch Adjani vainly try to fight Time and in the process resemble more and more a porcelain doll.

And that's the end of tonight's Star Watch.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Frances Faye revisited

You can't really go wrong with frantic bongos. Within a minute or so of Terese Genecco and her "little big band" taking the stage at the Metropolitan Room Saturday night, and as the manic percussion was launching the festivities, it was obvious the show would generate more wattage—and fun—than an entire evening of Rufus Wainwright at Carnegie Hall.

You can't really go wrong with frantic bongos. Within a minute or so of Terese Genecco and her "little big band" taking the stage at the Metropolitan Room Saturday night, and as the manic percussion was launching the festivities, it was obvious the show would generate more wattage—and fun—than an entire evening of Rufus Wainwright at Carnegie Hall.Following a tip from the esteemed Adam Feldman, we trekked to the Metropolitan Room (a very nice place to see a show, by the way) intrigued by the prospect of a singer brazen enough to pay tribute to Frances Faye, a spirited but now largely forgotten nightclub singer whose career spanned the 1930s–’70s. Most of Faye's dozen albums are out of print, and my introduction to her came only a few years ago through Caught in the Act, which documents a Vegas set complete with oddball banter. Oddly enough, Faye is absent from James Gavin's indispensable book on the New York cabaret scene.

As Genecco makes it clear, she doesn't try to impersonate Faye. Rather, she and her smokin' seven-piece band attempt to recreate the mood at Faye's shows; they use the same arrangements (many by Russell Garcia), replicate some of Faye's nuttier flights of fancies (like tweaking the lyrics to "If I Was a Rich Man" to "If I Had a Kilo") and Genecco actually uses some of Faye's between-songs bawdy banter. During the faster numbers, I was reminded Keely Smith but also of Anita O'Day's hard-swinging Songbook albums of the 1950s and 1960s, especially Anita O'Day Swings Cole Porter with Billy May and Anita O'Day and Billy May Swing Rodgers and Hart (the latter produced by Garcia). Genecco's diction was impeccable and she never got thrown off the runaway-train melodies; unlike Wainwright, who looked and sounded as if he was struggling against the songs, Genecco—who also played the piano on some tunes—was never less than supremely comfortable with the material. And the band looked as if it was having a blast, a statement in and of itself. Let's just hope New Yorkers will catch on enough to make it worthwhile for Genecco and her band to come back soon.

Friday, October 13, 2006

A hell of a show

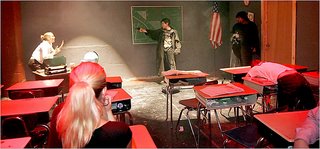

Les Freres Corbusier's Hell House at St. Ann's Warehouse is scary in several ways. The company that gave us Boozy (nominally about Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs, and one of my favorite shows of the past couple of years) bought a $300 Hell House kit from Pastor Keenan Roberts—who makes quite a nice chunk of change by selling them to churches who want to set them up for Halloween—and put it on with a straight face. Small groups of 10-12 people are led through a maze of interconnected rooms by a demon guide and for about 45 minutes we are exposed to what fundamentalist Christians think is scary: a girl is slipped a roofy at a rave, gets gang-raped and commits suicide; a cheerleader endures a bloody abortion; a student guns down his class, Columbine-style; two gay men get married to each other, then one of them becomes sick with AIDS and agonizes on a hospital bed (the doctor wears a yarmulke—nice touch); and so on. The production is pretty much identical to the ones staged all around the Bible Belt (though it would have been even more hardcore to import an actual Hell House complete with Christian extras); the difference is the audience, and how it perceives the Boschian tableaux.

To a proud daughter of the Enlightenment, the scariest part of Hell House is that there are quite a few Americans who take this superstitious nonsense seriously; not only that, but these smug, medieval obscurantists also feel they can tell everybody how to lead their lives. This Hell House may be designed to put the fear of god into fundamentalists—and I can only imagine how it must freak out/screw up a 14-year-old girl in the depths of Oklahoma or Colorado—but it certainly makes my secular-humanist blood boil with anger.

On a side note, Keenan Roberts' approach is very similar to that of fundamentalist cartoonist Jack Chick, whose illustrated tracts are popular kitsch items in many hipster-heathen household. Both men use popular culture to draw in their victims, and both display an uncommon amount of gleeful violence and luridness just as they make a show of demonizing these traits.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Missed opportunities

Considering how good the basic building blocks (book, music) in A Chorus Line are, I was frustrated by the futility of the new revival. I didn't see the original production, but everybody is in agreement that the "new" one is a slavish carbon copy. It was directed by Bob Avian, who co-choreographed the original; Baayork Lee was the original Connie and is now responsible for "choreography re-staging." Sure, it's very entertaining, and large parts of Marvin Hamlisch's score continue to send shivers down my spine, but what's the point?!?

In a weird way, A Chorus Line anticipated the reality-TV boom, with cast members talking to a director (i.e., the camera) in confessional mode, while going through a casting call (i.e. elimination process). It would have been great to dynamite the show and direct it from that perspective, like some kind of razzle-dazzle Big Brother series, but it would have taken producers with balls.

I am told there are legal reasons that A Chorus Line must be staged the same way it always is. This is the death knell for this show: It'll only endure as a period artifact preserved in formaldehyde. It could easily be staged as a biting commentary on a culture driven by ego that's both self-aggrandizing and self-pitying and by competition, but instead it remains a backstage musical frozen in 1975 amber. While this is fine—it's hard not to like a good backstage musical—it could also be…something else. One day, some British director will mount a production of A Chorus Line that brings it into the 21st century, and then everybody here will wonder why nobody had thought of it before. (Look at what John Doyle did to Sweeney Todd.)

The paucity of imaginative directors on the Broadway and upper-Off stages drives me up the wall. What's up with Scott Elliott, for instance? His Threepenny Opera on Broadway was clueless; now his Prime of Miss Jean Brodie for the New Group is a snooze. The play is full of exciting dark corners, especially in the way it deals with the confluence of teaching and domination, and the way it looks at how a charming, charismatic individual can bamboozle students into a miasmic ideology. But Elliott doesn't seem to have any point of view on the story, just as he didn't have any on Threepenny, and he contends himself with letting actors loose, hoping they'll pull through. (And when all else fails: nudity!) Alas, Cynthia Nixon (whose Scottish accent is just bizarre) is out of her depth from the get-go, lacking not only the steely undergirding required to play Miss Brodie, but also the haughty black humor the character displays at times. My neighbor was asleep within 20 minutes; lucky him.

In a weird way, A Chorus Line anticipated the reality-TV boom, with cast members talking to a director (i.e., the camera) in confessional mode, while going through a casting call (i.e. elimination process). It would have been great to dynamite the show and direct it from that perspective, like some kind of razzle-dazzle Big Brother series, but it would have taken producers with balls.

I am told there are legal reasons that A Chorus Line must be staged the same way it always is. This is the death knell for this show: It'll only endure as a period artifact preserved in formaldehyde. It could easily be staged as a biting commentary on a culture driven by ego that's both self-aggrandizing and self-pitying and by competition, but instead it remains a backstage musical frozen in 1975 amber. While this is fine—it's hard not to like a good backstage musical—it could also be…something else. One day, some British director will mount a production of A Chorus Line that brings it into the 21st century, and then everybody here will wonder why nobody had thought of it before. (Look at what John Doyle did to Sweeney Todd.)

The paucity of imaginative directors on the Broadway and upper-Off stages drives me up the wall. What's up with Scott Elliott, for instance? His Threepenny Opera on Broadway was clueless; now his Prime of Miss Jean Brodie for the New Group is a snooze. The play is full of exciting dark corners, especially in the way it deals with the confluence of teaching and domination, and the way it looks at how a charming, charismatic individual can bamboozle students into a miasmic ideology. But Elliott doesn't seem to have any point of view on the story, just as he didn't have any on Threepenny, and he contends himself with letting actors loose, hoping they'll pull through. (And when all else fails: nudity!) Alas, Cynthia Nixon (whose Scottish accent is just bizarre) is out of her depth from the get-go, lacking not only the steely undergirding required to play Miss Brodie, but also the haughty black humor the character displays at times. My neighbor was asleep within 20 minutes; lucky him.

Sunday, October 08, 2006

Everything old is new again is old again

Let's take two completely different offerings: Jay Johnson's The Two and Only on Broadway and Mikel Rouse's The End of Cinematics at BAM. I went to the former expecting little—after all, this was a one-man show by a ventriloquist whose main claim to fame was a recurring gig on the 1970s series Soap; yet I came out not only charmed, but musing about the evolution of popular entertainment, dichotomic acts, acting with voice vs. body. I went to the latter expecting to my brain cells to be activated, my sensory nerves to be tickled; I exited in a semi-catatonic state.